|

Nightmare

on the

Diamond Bar

New

Mexico

ranchers Kit

and Sherry

Laney won

awards for

stewardship.

As thanks

for their

good work,

and thanks

to the feds,

Kit was

jailed.

By

Susan

Christy

It's

been nearly

20 years

since Kit

and Sherry

Laney first

saw the

Diamond Bar

Ranch in

southwest

New Mexico.

They were

really just

kids then,

full of

dreams they

never

suspected

would become

a nightmare.

The

years have

aged them

now beyond

their

still-young

appearance

of only 43

and 42. But

it was not

from the

hard horseman's

work on the

roadless

ground that

crosses the

Gila

Wilderness.

It wasn't

the

sacrifices

they made of

ordinary

modern

conveniences

that tore

them apart

as a couple.

It wasn't

even the

gut-wrenching

bitterness

they felt

toward the

unfair way

they were

treated that

finally

brought Kit

to jail,

held

indefinitely

as a

political

hostage.

What has

changed the

once

idealistic

couple so

deeply and

forever are

the legal

betrayals

that pile up

higher

around them

than the

fines they

face for

trespass on

their own

ranch.

Intent

on

continuing

their

families'

tradition of

tending to

cattle in

Catron and

Sierra

county, Kit

and Sherry,

at 22, found

the

broken-down

Diamond Bar

unimpressive,

but in their

price range.

Stressed by

nature and

previous

tenants,

plagued by

periodic

drought that

left some

areas mere

tufts of

grass on

barren

ground, the

Diamond Bar

held an

1860s'

heritage,

but a recent

history of

neglect.

They thought

they had the

youth,

endurance

and optimism

to improve

and restore

the range,

and they

were even

encouraged

by a Forest

Service

Memorandum

of

Understanding

(MOU) for

the ranch

requiring

water source

development

that would

keep cattle

further away

from canyon

streambeds.

The Laneys

made a low

offer on the

place that

no one

thought the

bank would

take, but it

did. Diamond

Bar Cattle

Company and

Laney Cattle

Company were

in business

with a

permit for

1,188

head

in January

1986.

Sherry

remembers

that even

though they

were asked

to quit

making

improvements

for a time

because of

environmental

reviews,

ranching on

the Diamond

Bar was a

good life,

full of

optimism,

until about

1993. Four

years later,

in 1997,

they were

forced to

leave.

Diamond

Bar's

wilderness

area

prohibits

motorized

vehicles on

about 85

percent of

the range.

Elevations

on the

approximately

272 square

miles of the

ranch range

from 6,000

feet along

the Gila

River's

East Fork to

Diamond Peak

at 10,000

feet.

Temperatures

stretch from

subzero cold

in the high

canyons to a

low broil on

the summer

flats.

Trails are

steep, snow

can be belly

deep and

scrubby

vegetation

is just all

that's

there in

some places,

with or

without

cows. It is

a land of

challenges.

"Youâre

not going to

get up in

the morning

out here and

get in your

pickup,"

says Sherry.

"You're

going to go

saddle your

horse and

ride many

miles every

day."

Ride,

they did.

The Laneys'

perseverance

on the

Diamond Bar

earned them

an

Excellence

in Grazing

Management

Award from

the New

Mexico

section of

the Society

for Range

Management

in 1993.

Even the

Forest

Service

acknowledged

that forage

on 98

percent of

the

ranch's

grazeable

acreage was

in fair or

better

condition.

The Laneys

worked hard

to keep it

that way.

After ash

and sediment

from fires

choked

creeks, they

kept cattle

off

succulent

regrowth to

help the

watersheds

recover.

Thick trees

crowded

grasses,

drought

endured, and

no matter

what÷to

those who

only saw

without

understanding÷the

Laneys were

attacked,

their cattle

held to

blame.

In

retrospect,

environmental

advocates

began

protesting

the presence

of cattle on

the Diamond

Bar almost

immediately,

when

conservationists

of many

stripes and

agendas

began to

chafe at the

fact that

cows were on

"their"

public land.

Silver City

resident

Susan Schock,

admittedly

uncomfortable

among rough

stock

raisers in

her newly

adopted

home, had a

Forest

Service

friend over

for dinner

in 1987. He

told her

that the

Laneys

wanted to

build stock

tanks and

mentioned

that someone

ought to do

something

about it,

since it

could be a

violation of

the

Wilderness

Act. Schock

and her

friend Mike

Sauber

formed Gila

Watch to

block

construction,

alleging

that stock

tanks would

corrupt the

value of the

wilderness

they claimed

to know by

vicarious

sense.

The

Forest

Service

closed roads

and trails

in the

area

to bring in

a contractor

to gather

the Laneys'

cattle for

impoundment.

Using his

own road,

Kit got a

ticket for

not carrying

a permit.

Photo

by Zeno

Kiehne, The

Messenger

Gila

Watch placed

a full-page

ad in the

Albuquerque

Journal in

April 1995

showing a

bone-thin

calf on a

worn pasture

and claiming

that, "one

rancher

commands the

use of

145,000

acres of

the·wilderness

through the

ownership of

only 115

acres of

private

land. "The

ad coincided

with New

Mexico's

congressional

delegation

lending an

ear to a new

form of

grazing

permit Kit

Laney was

drafting to

recognize

private

rights to

water and

access to

the land. In

the urban

population

center of

Albuquerque,

the ad was

received

like it was

a

dolphin-free

tuna

campaign.

Confronted

with the

implied

opposition,

the Forest

Service

refused to

accept the

Laneys"

allotment

proposal

despite its

merit based

on direct

study of the

watershed.

The

fight was

on.

After

they built

the first

two upland

water

sources, as

required, by

the Forest

Service MOU

in the late

1980s, the

agency asked

the Laneys

to hold off

on any

improvements

for a year

so some

environmental

reports

could be

done. Then

the Forest

Service left

Diamond

Bar's MOU

out of the

Gila Forest

Plan in

1986. That

oversight

necessitated

an

evaluation

under the

litigation-friendly

National

Environmental

Policy Act (NEPA),

which has

been so

successfully

used by

environmental

organizations

to reduce

grazing on

public lands

that there

is now a

how-to guide

for it on

the Sierra

Club

website. The

environmental

evaluations,

most open to

wildly

non-scientific

public

comments,

meant that

the Diamond

Bar went

without

improvements÷not

for just the

year, but

until 1995

when the

Laneys were

abruptly

told to

reduce their

herd to 100

head, a

catastrophic

reduction in

their

investment.

After

appeals and

congressional

intervention

delayed that

decision, a

June 1995

Record of

Decision

authorized

just 300-800

cattle and

20 horses.

Appeals went

to deaf

ears.

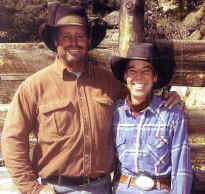

Kit

and Sherry,

in better

days.

They

took over

the Diamond

Bar

in

southwest

New Mexico

in 1986,

worked hard

improving

land and

livestock,

and won

awards for

stewardship.

In

repayment,

the U.S.

Forest

Service

put

them under

house arrest

and

surrounded

the ranch

with armed

federal

agents

wearing

bulletproof

vests.

Photo

by Willie

Shoemaker

By

the time the

Diamond

Bar's

grazing

permit

expired in

1996, the

Laneys

weren't

very

trustful of

the Forest

Service-the

agency had

not upheld

its side of

the

contract.

When their

proposed

alternative

permit was

denied,

Diamond Bar

Cattle

Company (DBCC)

filed suit

against the

United

States,

declaring

the ranch as

lawful owner

of water and

grazing

rights on

forestlands

within the

allotment.

In April

1997, the

Federal

District

Court ruled

in favor of

the U.S.,

dismissed

the

complaint

and ordered

the Laneys

to remove

their

livestock

and pay

grazing fees

for the

unauthorized

grazing

during the

litigation

period. An

appeal to

the 10th

Circuit

Court of

Appeals was

lost. As the

Laneys were

hopelessly

pursuing a

fair look at

their rights

in court,

the Forest

Service

called for

no grazing

at all on

the Diamond

Bar,

supposedly

due to

"extreme

overgrazing

during the

period that

DBCC's

lawsuit was

being proved

through

Federal

District

Court."

The decision

left open

the

possibility

of allowing

for possible

grazing of

300 cattle

and 20

horses at an

undetermined

future point

in time.

The

Laneys paid

the fines

and left the

Diamond Bar

in 1997.

They tried

to ranch for

four years

on a place

down at

Gila, then

on two

different

ranches over

at Logan.

Sherry says

it was six

years of

hell. Their

living

conditions

were meager.

Winters were

spent in a

summer cabin

with no

running

water. There

was nowhere

that they

could really

call home.

Both Kit and

Sherry kept

riding,

trying to

keep their

stock alive

and well so

that someday

they could

go home.

"We took

them off, we

paid all of

the fines.

They said

theyâd let

it rest for

three to

five

years,"

says Sherry.

Fines

were not the

only thing

that Kit and

Sherry paid.

They

divorced in

2000 and

Sherry broke

down,

emotionally

and

physically.

"I went

through a

lot of

physical

problems

that had

just been

building

up, "she

says. "I

was so give

out. I was

depressed.

Mainly, I

stayed at my

mom's for

two years

and I felt

like all I

did was

sleep."

Kit and

Sherry kept

in touch by

phone,

mostly

because of

their shared

cattle.

"The cows

kept us

together,"

Sherry says.

"I

didnât

want to get

rid of my

half and

couldnât

find a

lease, as

dry as it

was."

Kit

was there

for Sherry

when her

sister and

her

sister's

children

were

murdered in

July 2001.

They talked

through many

issues that

had gone

unnoticed or

ignored, and

finally they

reconciled.

Sherry

admits

ruefully

that though

she's

built

herself back

up, she just

can't work

as hard or

ride as hard

as she used

to.

But

there was

trouble to

come at the

Diamond Bar.

The Laneys

filed for a

permit for

300 head at

the Diamond

Bar three

times from

2001 to 2003

and, each

time, a

denial

letter came

in the mail.

"They

never say

why. They

didn't

even give us

lip

service,"

says Sherry.

"Just that

they

wouldn't

consider it

at the

time."

Range and

riparian

experts

called in to

assess the

Diamond

Bar's

suitability

for grazing

said the

allotment

was in

good-to-excellent

shape.

Environmentalists

dismiss

these

studies,

saying the

experts are

rancher-friendly.

Daily

ranch chores

continue

regardless

of

pressures.

Above

Sherry is

milking

Sugar.

Sherry's

sister Marie

helps sort

cattle.

Neighbors

have always

been

supportive,

but one has

been missing

over the

past few

years. Gila

Permittees

Association

President

Laura

Schneberger

recalls that

the Forest

Service and

ranchers

"used to

be

neighbors.

The Forest

Service used

to sit down

with

ranchers to

write Annual

Operating

Plans. Now,

they issue

edicts that

ranchers

must comply

with."

If

you listen

for awhile,

itâs

readily

apparent

that the

Laneys are

by no means

the only

ranchers

having

problems

dealing with

unrealistic

management

from an

agency that

has chosen

to favor

environmental

agendas

rather than

the people

on its land.

Especially

targeted are

those near

the

wilderness

area, long

considered

to be a

lynchpin in

the

formulated

Wildlands

Project

meant to

remove human

presence

from as much

as one-third

of the North

American

continent.

In

February

2003, Kit,

Sherry and

friends

found hope

in the case

of Wayne

Hage, who

has

successfully

waged a

20-year

battle for

vested

rights on

his ranch in

Nevada. Kit

Laney and

Wray

Schildnecht,

an

exhaustive

researcher,

familiarized

themselves

with the

Hage case,

poring over

law

dictionaries

and books on

private

property

rights. It

gave them

hope that

the Diamond

Bar too

might win in

court

someday. But

Hage, in a

coldly

intellectual

manner that

few

understand,

usually

cautions his

followers to

patience.

The Laneys

hardly had

such time.

At

the time,

Sherry says,

"We were

pretty

tapped out.

On one

place, they

gave us two

weeks to pay

double on

our lease.

There

wasn't

anyplace in

the world

with any

grass,

except the

Diamond Bar.

We thought,

there's a

world of

grass out

here, why

don't we

use it?"

Armed with

Hage's

inspiration

and working

to simplify

the matter

of

preexisting

water,

property and

use rights,

the Laneys

disbanded

the Diamond

Bar Cattle

Company and

filed in

Catron

County for

their rights

in the form

of a deed.

Since the

company had

lost it all,

Kit and

Sherry's

recourse was

to form a

warranty

deed and

file for

their

property as

individuals.

In

April 2003,

Kit and

Sherry moved

home to the

Diamond Bar.

One night, a

local ranger

called the

house and

said the

Forest

Service

wondered

what their

intentions

were. Sherry

told him

simply,

"We intend

to use our

private

property."

Environmentalists

began

visiting the

Diamond Bar

and

reporting

what they

saw as

livestock

damage to

Gila Forest

Supervisor

Marcia

Andre. In

June, the

U.S.

Attorney's

office filed

to enforce

the 1997

decision to

remove

cattle from

the Diamond

Bar due to a

lack of

permit.

Federal

Judge

William P.

Johnson

ruled in

Albuquerque

in December

2003, that

Diamond Bar

Cattle

Company, and

Kit and

Sherry

Laney, were

in contempt

of the

previous

court order

and gave

them 30 days

to remove

their

cattle.

The

ruling was

good news

for the

National

Wildlife

Federation (NWF),

Center for

Biological

Diversity,

Gila Watch,

New Mexico

Wildlife

Federation,

Trout

Unlimited

and

Wilderness

Watch. After

reactivating

and updating

their 1996

motion to

intervene,

which came

too late

that time,

the groups

asked for an

injunction

last fall

for

immediate

cattle

removal from

the Diamond

Bar. They

were

recognized

as

interveners

just two

days before

the

judge's

December

decision.

Negative

editorials

about the

Laneys and

the range

conditions

on the

Diamond Bar

read word

for word

from

environmental

organization

press

releases.

Claiming

that the

U.S.

Attorney's

trespass

charge

against the

Laneys

"didn't

show the

extensive

damage being

caused by

cattle,"

NWF staff

attorney Tom

Lustig said,

"we

intervened

to show the

court that

the ongoing

trespass was

causing

substantial

environmental

damage."

Pictures

disagree.

Gila

ranchers say

that

environmentalists

know just

where to go

to get the

pictures

that they

want. Point

the camera

100 yards in

another

direction,

says

Schneberger,

and you"ll

get thick,

high grass.

"One

hundred

yards from a

tank,

everything

is fine.

When you

have cattle

that need

water, areas

near it will

get heavy

use. Kit and

Sherry tried

to develop

water

sources to

keep the

cattle out,

but they

[environmentalists]

sued."

Pictures

taken by the

Center for

Biological

Diversity

and their

friends

point to a

cozy

relationship

with the

Forest

Service.

After

visiting

South

Diamond

Creek for

two days in

July, the

Center sent

Andre photos

of cows,

noting

"cow

manure

everywhere"

and

complaining

of trails

that were

"pounded

to fine dust

with cattle

hoof marks

everywhere."

Lustig

crowed that

once the

Laneys are

off the

ranch, the

agency would

inspect for

damage,

tally the

costs and

charge Kit

and Sherry

for stream

degradation,

replanting

of wild

grasses and

anything

else they

could find.

The

Forest

Service has

already done

worse. The

contractor

they hired

to impound

the Laneys'

cattle was

no cowboy.

Guarded by

40 or so

armed Forest

Service

personnel,

the ranch

was

crisscrossed

by

helicopters

in early

March

searching

for cattle.

Roads and

trails were

blocked, the

Laneys were

watched as

trespassers

on their own

ranch.

Other

ranchers

went to the

New Mexico

Livestock

Board to ask

for help

after word

spread that

no auction

in New

Mexico would

sell the

Laney cows.

"That

hearing was

the first

time I've

ever seen

all of the

New Mexico

livestock

industry

together on

one

issue,"

Sherry

states. At

issue was

the MOU that

Dan

Manzanares,

the

board's

executive

director, signed

with the

Forest

Service,

authorizing

the removal

of the

Diamond Bar

cattle. The

agreement

was signed

before the

board was

consulted,

purportedly

on orders

from

Governor

Bill

Richardson.

Paragon

Foundation,

a private

property

rights group

in

Alamogordo,

N.M., that

has helped

the Laneys

before,

filed for an

injunction

to stop the

impoundment.

The

impoundment

was over

before it

could be

heard.

The

outside

world hears

news long

before it

reaches the

ranch house

at Black

Canyon, so

there was no

preparing

for what

came next.

Kit, Sherry,

Kit's

brother

Dale, his

wife and son

tried to

conduct

business as

usual when

the feds

moved in,

but it was

unnerving.

"Weâre

under house

arrest,"

Kit reported

at the time.

They saw

only

automatic

weapons,

bulletproof

vests, and

the

ineptitude

of the men

gathering

their cows.

Two camps

were set up,

where

spooked

officers

came

spilling out

of cabins

and RVs if

an

unauthorized

vehicle

happened by.

Friends

could not

visit. The

media was

not welcome.

Kit got a

ticket going

to town one

day just for

not having a

travel

permit.

Everyone got

hassled.

Harassment

escalated

when the

Laneys got

too

close÷no

pictures, no

interference.

It

was uneasy

as Kit and

Sherry

continued to

ride and

tend to

their

cattle.

Topping out

on a ridge

one

afternoon

they saw

something

bright

orange in

the draw

beneath

them. When

they saw the

Forest

Service

truck, they

realized the

orange poles

formed the

impoundment

pen. Kit

wanted to

take a look,

not trusting

the

contractorâs

head count

of the

cattle being

rounded up.

He was also

concerned

that cows

were being

gathered up

without

their

newborn

calves. The

contractor

and crew

from Rio

Arriba were

breaking all

ranch rules,

leaving

every gate

open behind

them.

On

Sunday,

March 14,

Kit and

Sherry split

off onto

different

paths. Kit

was going to

spend the

night in a

neighbor's

cabin on the

East Fork

and Sherry

was going to

meet him

there Monday

morning.

Late Sunday

night, she

got a call

from Mary

Miller, a

friend who

was staying

at the Links

(Diamond

Bar's

second

parcel of

deeded,

private

land). She

told Sherry

there was a

weird

message on

the ranch

answering

machine from

the

Wilderness

District

saying one

of the

Laneys'

horses was

at Trails

End. Sherry

and Mary

couldn't

think of any

missing

horses. They

even called

neighbors,

who

weren't

missing any

either.

Jokingly,

Sherry told

Mary, "You

don't

reckon they

arrested Kit

and took his

horse?"

By

the time she

went to bed,

Sherry had

decided it

was a

mistake and

wasnât her

horse. And

what could

Kit get

arrested

for? It was

an absurd

thought.

Monday

morning, Kit

wasn't at

the East

Fork. There

was no sign

of him; he

hadn't

spent the

night there.

Sherry went

on a

marathon

ride,

thoughts

racing

faster than

her horse.

Was he hurt?

What did

they do to

him? Was he

alive? What

could

possibly

have

happened?

She rode for

12 miles.

When she hit

his

horse's

tracks about

halfway

through, she

could tell

where he had

headed: to

the bright

orange

corral,

where she

followed,

but found no

horse. She

just knew

before she

got there.

At Links,

meanwhile,

the Forest

Service was

telling

Miller that

Kit was in

jail.

At

his first

detention

hearing

where he was

represented

by a

court-appointed

attorney,

Magistrate

Judge Karen

Molzen

acknowledged

that Kit

Laney had no

previous

record, nor

was he a

flight risk.

She kept him

in jail over

concern that

he could be

a danger to

law

enforcement.

Forest

Service

Special

Agent

Douglas

Charles Roe

testified

(secondhand,

since he

wasnât at

the corral)

that Kit was

violent,

yelling

obscenities,

charging his

horse at

federal

officers,

whipping one

with his

reins. Kit

has never

been known

to cuss, and

doesn't

tolerate it

well from

others.

Still, he

concedes to

friends that

"SOBs"

came

bursting out

of him like

something

he'd

forgotten

he'd

swallowed

when he saw

the way his

cattle were

being

penned, cows

locked away

from calves,

no care

taken. He

would have

needed

nine-foot

reins to be

whipping

anybody, Kit

said, but he

doesnât

deny riding

up close to

open the

pens before

his horse

was struck

with a

flashlight

and he was

dragged down

in a cloud

of pepper

spray.

After

Kit's

arrest, he

was charged

with assault

and

interference

with three

federal

officers.

Less than

two weeks

later, it

escalated

into an

eight-count

federal

grand jury

indictment

that

involved

five federal

officers and

could bring

fines of

$2.7 million

and 51 years

in jail. A

motion to

reconsider

his

confinement

was denied

March 24,

"until the

impoundment

is

finished."

The Diamond

Bar cattle

were

actually

shipped out

that night.

No one could

(or would,

under threat

from the

Forest

Service) say

where they

went.

The

impoundment

wasn't

over with

the cattle.

Before she

left the

Diamond Bar

on March 25,

Sherry had

planned to

take her

pack horses

out to

family and

friends, but

by the time

she returned

to Black

Canyon two

days later,

they were

gone. The

Forest

Service says

they were in

trespass.

That relates

to another

issue

that's

never been

resolved

after years

of

mediation.

Never

surveyed,

the Forest

Service has

contended

that Diamond

Bar's

deeded land

is up the

side of the

canyon from

where the

Laneys'

house sits,

built onto

in the 1930s

and adjacent

to the

original

1880s'

bunkhouse.

Contractors

came into

the canyon

from above

the house,

not by road,

and either

opened the

gate and

waited or

just herded

the horses

straight

from the

pen. Without

the saddle

horses,

daily work

canât get

done on the

Diamond Bar.

A few mares

were all

that were

left on

Diamond

Creek.

Sherry

missed a

packed

fundraiser

for Kitâs

legal

defense at

Uncle

Bill's in

Reserve,

N.M. that

night as she

continued to

work on the

horse issue.

The Forest

Service

reportedly

wanted $650

to feed them

overnight

but later

released

them at no

additional

cost. Catron

County

Sheriff

Cliff Snyder

was expected

to get

involved,

though the

Forest

Service had

largely

ignored him

while they

raided the

Diamond Bar.

Hardscrabble

fighter

isnât an

accurate

description

of Kit

Laney.

Tenacious,

even

bullheaded,

is. Polite

in an

environment

where

thatâs not

so unusual,

he's even

thought

about just

giving up.

Spurred on

by Sherry,

other

ranchers and

friends with

backgrounds

in private

property

rights, Kit

refuses to

just walk

away from

the Diamond

Bar. Jail is

a waste of

time.

Government

attorneys

intend to

show Kit

that he

can't

thumb his

nose at a

court order.

He intends

to fight the

courts to

prove the

vested

rights he

and Sherry

own.

Sherry's

visits with

Kit in jail

find that

he's

frustrated,

but OK.

He's read

all of the

Louis

L'Amour

books twice

and is

restlessly

lapping the

rec room.

Tides

could turn.

So far, the

Laneys have

been

successfully

marginalized

as extreme,

hateful,

antigovernment

radicals in

the

mainstream

press.

Environmentalists

are

overjoyed

that their

PR campaign

against the

Diamond Bar

is a success

and news of

the

supposedly

impertinent

Laneys is

generally

accepted by

urbanites

ignorant of

ranching.

But the

Forest

Service

continues to

play games,

telling the

press that

the Laneys

can buy

their cattle

back within

five days

and they

know it.

Kit's in

jail,

receiving

little or no

information.

The only

notice

Sherry got

were flyers

posted on

ranch gates.

Paragon

Foundation

and the Gila

Permittees

Association

are

accepting

donations:

Paragon for

legal fees

and the

association

for expenses

while Kit is

"indisposed."

Support from

friends,

Paragon,

Wayne Hage,

his wife

Helen

Chenoweth-Hage

and a

sympathetic

public are

not all the

Laneys need.

Even though

they don't

trust

lawyers much

after losing

in court so

many times,

what they

need now is

a criminal

defense

hotshot.

Twenty

years of

tough

ranching

terrain,

every day

with the

hardship of

a continuous

losing

battle with

the Forest

Service and

nearly every

antigrazing,

clean-water-loving,

forest-guarding

organization

and concern

in the

country,

haven't

stopped the

Laneys.

They've

lost in

court; lost

their faith

in courts

and lawyers;

divorced;

endured

tragic

family

circumstance;

reconciled;

and faced

tremendous

amounts of

stress. But

Kit and

Sherry are

committed,

first to

proving

Kitâs

innocence

before the

grand jury,

then to

proving

their

private

property

rights, even

if it means

they won't

be able to

keep their

home on the

Diamond Bar.

If not,

another

ranch

someday,

they hope.

"They take

and take and

take,"

Sherry says,

"and if

they can

take this

away from

us, what's

to stop them

from doing

it to

anybody

anywhere?"

Susan

Christy is

the former

editor/publisher

of The

Courier, an

independent,

weekly

regional

newspaper in

Hatch, N.M.

To help the

Laneys,

contact

Paragon

Foundation

at

887-847-3443

<paragon@wayfarer1.com>

or Gila

National

Forest

Permittees

Assn. at

P.O.Box 186,

Winston, NM

87943.

SIDEBAR

Tyranny

Poses As

Justice

In

the name of

liberty...Kit

Laney.

By Tim Findley

In

a free

society,

there is

nothing more

chilling to

the soul or

inflaming of

the heart

than tyranny

posing as

justice.

Kit

Laney is a

political

prisoner.

Put aside

for a moment

the

overdrawn

comparisons

to Nazi

Germany or

Stalin's

Soviet

Union: Laney

is an

American

political

prisoner

even if his

iron

shackles

have been

removed.

Known

terrorists

were

afforded due

process and

released in

less time

than Laney

was granted

his rights

by a petty

and

politically

reliant

federal

magistrate.

Murderers

have in some

cases been

released on

bail with

less

resistance

than that

shown by the

"powder

kegä

hyperbole of

an

opportunistic

federal

prosecutor.

Laney

committed

the greatest

political

crime of all

in that New

Mexico

regime of

federal

demagogues

and bullies.

He resisted.

The

federal

government

there is

afraid of

Kit

Laney's

freedom.

They are not

afraid of

Kit himself

whom they

know as many

of us do to

be a

generally

quiet,

overly

polite man

who may

never have

won a fight

in his life,

let alone

picked one.

It isn't

Kit that

scares them.

It's

Kit's

liberty they

fear.

So

long as

Laney can be

criminalized

and

demonized by

the

posturing

jackals of

injustice in

federal New

Mexico' his

personal

freedom

cannot

threaten

them. They

are not

afraid of

Kit. They

are afraid

the rest of

us might

emulate his

simple

courage to

be free.

And

that is the

way it was

done at the

beginning in

Berlin or in

the darkened

villages of

the Ukraine.

Take one

first as a

hostage to

freedom and

intimidate

the rest

until they

are willing

to go

quietly

without

resistance.

It

has been

done before

in this

country

too-in the

crushing of

organized

labor in the

1930s, the

"red"

smears of

the 1950s,

and the show

trials of

antiwar

activists

and Black

Panthers in

the 1960s.

Every

outrage of

political

repression

has left a

legacy of

contempt and

hatred for

those who

cloaked

their

oppression

in official

robes.

This

will be no

different.

If it were

another

time, these

same people

who

destroyed

Laney's

livelihood,

who

shattered

his family

and robbed

him of his

rights,

might have

been hunted

down as the

thieves and

rustlers and

corrupted

political

sycophants

that they

are. The

jackbooted

thugs who

waited to

trap him

like the

gestapo on a

train might

themselves

have been

brought to

trial.

Laney

is only

someone

these

perversions

of justice

want to

punish. He

is their

symbol to

bear the

cross and

frighten the

others into

submission.

Kit Laney is

the

frightened

whisper they

hope to hear

spreading

among any

others who

might dare

think of

resisting.

Shall

we accept

that and

cower until

they come

for us? Or

shall we

face them

with what

they fear

most? Kit

Laney's

name spoken

loud and

clear. Kit

Laney posted

as a simple

sign on

every fence

post or

written

large across

a barnyard

roof. Kit

Laney. On

the marquee

of the

coffee shop

or the

hardware

store. On

the back of

pickup

trucks and

long-hauling

18-wheelers.

No threats,

no demands,

just two

words-Kit

Laney.

Remind them

everywhere

they go that

we know what

scares them

most, and

that they

themselves

have given

it a name.

Kit Laney.

Let

us then see

what legacy

survives

this episode

of

politically

motivated

arrogance

and

oppression.

Will it be

the chill

they placed

upon our

souls or the

flames upon

our hearts?

Or will it

be simply

stated in

the peaceful

name of

justice and

liberty as

that which

seems to

frighten

them at last

more than

us. Kit

Laney.

As

a reporter

for The San

Francisco

Chronicle

and Rolling

Stone

Magazine,

Tim Findley

covered many

of the

"political"

trials of

the 1960s,

including

that of

Black

Panther

co-founder

Huey Newton,

the

so-called

"Chicago

Seven"

accused of

inspiring

riots in

Chicago, and

the

'Soledad

Brothers'

prison

cases. His

work during

Berkeley,

Calif.,

confrontations

over

"People's

Park" was

credited

with

prompting

dismissal of

charges

against some

400 people

rounded up

in one mass

arrest.

LATE

NEWS...

After

being held

without bail

for 25 days,

Kit Laney

was released

from jail in

Las Cruces,

N.M., on

April 8.

Still a

hostage, Kit

is in the

custody of

Otero County

rancher Bob

Jones of

Paragon

Foundation.

Kit is being

electronically

monitored

and may not

stray from a

10-mile

radius

around

Jones'

ranch. While

he was

detained on

five counts

of assault

on a peace

officer and

resisting or

obstructing

officers

executing a

federal

order, 252

head of

Diamond Bar

cattle were

sold at

auction in

Oklahoma for

$121,000 and

the Forest

Service had

shipped

another 162

head to the

sale barn.

Laney is

scheduled

for a

federal

trial in

Albuquerque

on May 3.

Summer

2004

Contents

|