| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] | |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

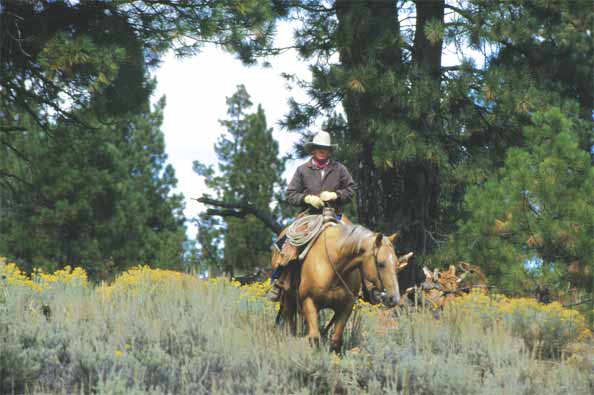

John O’Keeffe loves what he does. “You’re feeding a nation,” says O’Keeffe, 45, a third-generation cattle rancher from Adel, a tightly knit ranching community in southeastern Oregon. “That’s a noble thing to do if you want to look at it in philosophical terms. The only way to extract food from the range is by grazing livestock. You can’t plant cornfields. I firmly believe ranching is sustainable and appropriate.” He describes the O’Keeffe Ranch as an “average” Hereford-Angus cross cow-calf family operation with several hundred mother cows. The ranch includes 14,000 deeded acres and has permits on 100,000 acres of private and federal lands. He employs two or three full-time cowboys, seasonal help and relies on his family. His wife, Jane, helps with the bookkeeping while their sons, Henry, 17, and Patrick, 15, have been raised on a diet of ranch life. Like his sons, O’Keeffe has lived and worked on the family ranch near Adel his entire life. He credits his father, Henry, who died in 2001, with shaping his beliefs. “I learned a lot from him about the livestock and the hay and irrigating and life in general, like people do from their dads.” O’Keeffe learned about ranching on the job and at school. He earned a degree in agricultural economics from Oregon State University in 1980. “The knowledge background you get is real important,” he says of college. “There are a lot of days you might not use something, but that education gives you a base you can build on.” O’Keeffe continues to use that knowledge base. Ranching, he’s found, is an ever-changing process. Some changes are evolutionary, like changing from loose hay to round bales, from stock trucks to gooseneck trailers, and from riding horseback to driving motorcycles. But other changes involve science and politics. Ranching used to be about cattle and range management. In recent years O’Keeffe has seen that understanding livestock and their habitat is just part of the job. An increasingly larger consideration, one that demands more of his time and energy, is the politics of ranching. The O’Keeffe family held a summer grazing permit at the nearby Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge since 1954. Eleven years ago, when the refuge revised its management plan to exclude cows, the family scrambled to locate alternative grazing lands. “We made several adjustments,” he says. “It all cost money.” O’Keeffe doesn’t just fret and complain. He remains a rancher, but fewer days are spent at the ranch, even fewer in the saddle. “Somebody’s horseback 200 days a year on a ranch our size. Nowadays it isn’t always me. I do what I need to do, whether it’s cowboying or haying or irrigating.” O’Keeffe depends on family and hired help more than he might because he spends about 20 nights a year away from home representing cattle-related interest groups, such as the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association as vice-chairman of its federal lands committee. He’s also chairman of the Public Lands Council Task Force on Sage Grouse.

“We accomplish things,” claims O’Keeffe, referring to advocacy roles and ongoing contacts with government agency officials about such issues as grazing regulations. “One of the biggest values we provide is serving as an opponent to irresponsible environmental groups. If there wasn’t anybody to counter their outlandish claims, they might have more credibility.” His political involvement requires time and travel. And more time than he likes is spent in meetings. “I could do a lot more good if I had more time.” He needs to balance time spent on regional and national issues with managing his own ranch. “The need’s there,” he says of taking an active role in political issues, “but it can lead itself to burn-out.” Among his concerns is the possible listing of sage grouse as rare or endangered. In the 1990s, environmental groups claimed declines in sage grouse, which they call the “spotted owl of the sagebrush sea.” If sage grouse are listed, O’Keeffe says it will create an added layer of bureaucratic activity to grazing issues, and possibly lead to court decisions that could eliminate grazing on huge areas of the American West. “Environmentalists want to make sage grouse the poster child for removing livestock from sagebrush country. Andy Kerr and Mark Salvo, of American Lands, are trying to spin it, but it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.” Studies by biologists for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) and other government agencies indicate that other factors play significant or larger roles than grazing. “That interaction with livestock on well-managed land is not what’s creating a loss of sage grouse. Biologists say that removing livestock won’t help sage grouse return. It’s more complicated than that.” While O’Keeffe acknowledges that in the past some grazing practices harmed federal lands, he says some groups are using sage grouse or other issues as a pretext for ending livestock grazing, not necessarily to improve range lands. “Some environmentalists are misguided. They believe the propaganda. Some just don’t like livestock and they want the land the way it was pre-European settlement. There’s a core group of the radical ones who have sworn to remove livestock from federal lands.” His concerns about sage grouse partly stems from his family’s bitter experiences at Hart Mountain. “I probably didn’t see it coming as soon as I should have,” he says of FWS efforts to close the refuge to grazing to benefit pronghorn antelope. Permittees made various proposals, including a “wildlife friendly” plan that would have cut back grazing by nearly two-thirds. He claims they were never seriously considered. “It just shows you what their mind-set was—to get the livestock off and keep them off. Was it preordained? It sure appeared that way.”

Environmental groups, including the Oregon Natural Desert Association, say that increases in pronghorn antelope numbers at the refuge, especially in the past three years, stem from the removal of livestock. O’Keeffe says that argument ignores other factors, such as weather variables (a multi-year drought ended as the policy was enacted), and declines in coyote populations. “A lot of people want to point at Hart Mountain and use it as a showcase for how well wildlife can do when livestock are removed. They’re trying to spin the livestock removal as a success story.” In 1995, two years after livestock were removed, the fawn survival rate at Hart Mountain was .8 per 100 does. Over an extended time period, a survival rate of 25 to 30 fawns per 100 does is needed to keep herd rates constant. In 2003, the ratio was 50 per 100. More surprisingly, sage grouse numbers at Hart Mountain and the nearby Sheldon National Antelope Refuge in northwestern Nevada also increased. More than a thousand roosters were counted in 2003 at sites on the two refuges, an increase of 138 from a year earlier. Mike Nunn oversees Hart Mountain and Sheldon for FWS. He supports decisions made by his predecessors to remove livestock from Hart Mountain, but says it’s impossible to pinpoint a single factor that benefited pronghorn and sage grouse numbers. “In my opinion,” Nunn says, “the fact that the drought ended definitely was a benefit to the refuge’s habitat and wildlife, and removing the cattle definitely was a benefit.” O’Keeffe claims that various factors helped reverse then-declining pronghorn and sage grouse populations. “That’s a valid argument,” Nunn says, “I can’t prove or disprove it. The ranchers had a good grazing program. It was not just a turn ’em out and not see ’em again plan, it was a well-managed grazing program.” Along with removing livestock, the 1991 decision resulted in the removal of 240 feral horses, the seasonal closure of miles of roads in sensitive pronghorn habitat, the burning of 20,000 to 30,000 acres of targeted range lands, and the removal of 120 miles of fences. Nunn says a new Hart Mountain management plan, due out later this year, will “have the best science that’s available, but it’s not going to say the removal of grazing has been the difference.” O’Keeffe appreciates Nunn’s comments but says ranchers face an array of challenges, some known and others that will likely be surprises. It all creates an atmosphere of uncertainty. He’s unsure, for example, whether his sons will carry on the family ranching tradition. “It’s a little soon to tell, but I hope they’ll have the opportunity. They’re real active at the ranch now. They’re hard-working country kids.” Regardless of that future, O’Keeffe is proud of his children, his heritage, and proud to be a rancher. “I enjoy the life. The type of people you work with is a real benefit,” he says. “I think it’s a challenge. I wouldn’t feel right walking away from it. Ranching is a real rewarding life, not always financially. The work’s satisfying. Whether it’s haying or working livestock, you can see the results of your labor.” Lee Juillerat is a reporter/writer/photographer for the Herald & News in Klamath Falls, Ore. He is a regular contributor to RANGE. |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |