|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cleaning up around the house recently, I came across an old, crumpled receipt that instantly sent me reeling through memories of my first, and only, fishing trip. Last year, my friend Mark flew into Albuquerque from Los Angeles. I hadn’t seen him in ages, and after a frantic stop for gear and fishing licenses at Wal-Mart, we were eager to escape. I was especially eager to show him the natural splendor of my adopted home state. Tearing across Interstate 25 out of Albuquerque in my truck, we headed to Heron Lake in northern New Mexico in a peculiarly frenzied state of mind. We clung to the mental image of a 14-inch trout sizzling in a frying pan, resisting a conditioned urge to stop for fast food in Española, and proceeded full speed ahead. In contrast to our indecision at which brand of hooks to buy and what kind of tackle to bring, the southern Rockies loomed on the horizon ahead of us: clear, strong, tangible symbols of our escape. Our thirst for adventure increased with the elevation as we rolled through northern New Mexico, where grasslands, desert, and mountain converge upon each other in dreamlike, geomorphic episodes. The layers and textures of earth transformed before our eyes as we passed over them. To the west, frozen cascades of orange sandstone tumbled over stratified red mesa walls. To the east, deep green coniferous forests opened into rolling emerald meadows flecked, as if by brush strokes, with the blue-gray sages on the untrammeled high desert prairie. And to the north, two spry 28-year-old guys sped across the country with the windows open full, singing along with the Stones’ “Exile on Main Street” on a blaring tape deck, raising the head of more than one cud-chewing bovine. “Thank you for your wine, California. Thank you for your sweet and bitter fruit.” In preparation for the short interval before we would be enjoying fresh fish, we stockpiled hot dogs, chips, and beer. After all, people from large cities can become fidgety when they first settle into a place where buildings—representing the promise of modern conveniences—do not dominate the landscape. Weaving through a stand of pines on a dirt road, we approached our destination in silent awe of the San Juan Mountains that gently enclose the massive, 6,000-acre reservoir as if it were a sacred jewel. This large mirror—the turquoise-tinted Heron Lake—ûreflected the ridges and crags beneath the skies. Clouds sailed swiftly over the water’s surface. Outdoor writer Craig Springer once described the low-sloping, mountainous heaps scattered around the lake as a “huge purple armada, cruising nowhere.” In this setting, it did not take long to begin imagining the world had suddenly stopped. Our thoughts, of course, like one-way streets, led us naturally to our apprehensions. If we were here, left to our devices, stranded, to fend for ourselves, would we be survivors? Or would natural selection take us out of existence? My difficulty stringing a line through my rod inspired my immediate doubt. For his part, Mark was perplexed by a product called PowerBait—tiny, rubbery, synthetic, neon-pink balls somehow engineered to attract trout. They would consistently fall off the hook before the line was launched, only to become instantly lost in the shadowy fissures of the shale-littered shore. But we remained determined to partake in the activity that had sustained numerous civilizations throughout time, nourishing people who hunted in waters that, unlike Heron, were not stocked for the specific benefit of anglers with upward of a million fish each year by game and fish wardens. In contrast, we were a pair of young men who had at their fingertips all the advantages of the 21st century. Even so, after a few hours we resigned ourselves to a dinner of hot dogs and began planning the stories we’d tell when we got home: stories about reeling in mammoth sea creatures, stories illustrating our fitness for survival. Our adventure was beginning to resemble some of the characteristics of our actual lives: the determination to succeed, the will to give up quickly, and the unabashed resolve to fabricate information in order to save face. The following day opened with more promise. At eight in the morning the lake was serene and motionless. Our hopes were instantly renewed when Mark reeled in a tiny, baby trout, which we sympathetically tossed back into the water. But throughout the rest of the day, we would have no luck. We tried different spots; we varied our techniques; we dipped our lines in the shallows and we waded hip-high into the ice cold water; we removed our floaters only to lose a lot of hooks to the rocky lake bottom. As we ambled around hour after hour at the threshold of a vast and deep water world, answering to the call of stubborn determination, we could not manage to draw any fish. I began to wonder if there was some sort of

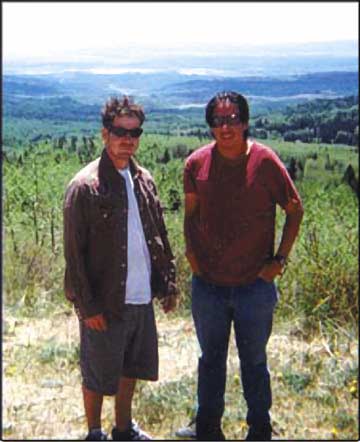

wisdom we were lacking in our approach, a spiritual net required to sift sustenance from the physical world. Just before sunset, we retired to shoot the breeze, moan about the sunburns we both acquired, and watch the last few sails drift across the opposite side of the lake. Days are long outdoors, and this one culminated in stunning visual theatrics that played out in the sky at nightfall. As the sun sank, an electric-pink hue tinted the sky and colored the mountain scenery, painting the nowhere-cruising armada an even deeper purple. Next a layer of electric blue appeared, shouldering out the light by degrees and then hovering and hesitating in ever-darkening brilliance. In moments, a single star in the powder blue sky spawned a billion stars blinking across a black-tar canvas. On the final evening of our expedition, as this ritual climax unfolded yet again and the stars began to multiply and sparkle, the evidence was not in our favor. We conceded. We were not anglers. Between the two of us, we caught one miserable four-inch trout. Nevertheless, living in the simpler, unconfined conditions of the outdoors, we became closer to the basic elements which afforded that sweet luxury of reflection. To my delight, I came to accept things as they were. Together, we could laugh that we had ourselves been cast into some murky waters and had not been devoured altogether. I met Mark nearly a decade ago at a party in a dingy apartment in Los Angeles, the home of a mutual friend who bore on his arm a tattoo of rosary beads attended by the cursive avowal that “Life is a Ritual.” Camping beneath this same multitude of stars, it felt that we’d come a long way; that we were somehow more adept at proceeding through this “ritual”; that we were, in fact, fit to survive, even if the trout weren’t biting. And I slept like a man who had wrestled and conquered a thousand fish that day. Almost a year later, here in Albuquerque, a grin spread over my face as I thumbed over what seemed to be an appropriate memento marking the close of life in my 20s: PowerBait, four cans, $2.99 apiece; 10-pound fishing line, $2.99; 7 varieties of hooks, $1.29 each; 12-quart Igloo cooler (to store our catch), $14.99; Shakespeare-brand auto-reel fishing rod, $32.99, Wal-Mart Bonus Buy. Ben Ikenson (at left in photo) is a speech writer for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in Washington, D.C. |

||||||

|

Winter 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||