|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

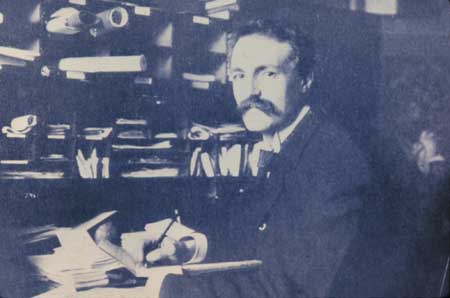

Family wealth freed Gifford Pinchot to pursue a career and notoriety in a field largely unknown in the United States: in October 1899, after graduating from Yale, he sailed to Europe to become a forester. Pinchot was handsome, tall and lean, with erect bearing. At age 23, with wrangled letters of introduction, he entered France’s École Nationale Forestière where he was impressed with concepts of efficiency and rational planning. Stifled by the classroom, he spent six weeks in Switzerland learning about “practical forestry.” The driven young man had the personality, innate political instincts, social connections, and chutzpah to successfully be the moving force to bring practical forestry to America. After 18 months of study, he returned to the U.S. as a forester. Coincidentally, an amendment to the Act of March 3, 1891 passed Congress with little notice. “For the Repeal of the Timber and Stone Act and for other purposes” gave the president authority to set aside forest reserves from the public domain. By 1897, 38.8 million acres were so designated. Pinchot knew these reserves were off-limits to use but, as there was no provision for protection or management, the reserves were subject to every-man-for-himself exploitation. Over the next eight years, Pinchot focused on becoming head of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. His first move was to gain practical experience as forester for the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. He then served briefly as a consulting forester and as secretary of several high-powered commissions dealing with forestry and public land issues. Astutely, he recognized that as secretary he had leverage over results and attention from those in high places that he could not otherwise command due to his youth. Most important was service on the National Academy of Sciences’ National Forest Commission, established in 1896 partially due to his efforts. He was not a member of the academy and he cultivated an acquaintance with naturalist John Muir, who was serving as observer. Muir and others on the commission, including head Charles Sprague Sargent, visualized forest reserves protected by the U.S. Army. Pinchot and geologist Arnold Hague thought the reserves should be used for the public good and managed by a professional civil service. The Commission’s report urged President Grover Cleveland to

maintain and add to the forest reserves; close them to all development save mining and timber harvest; and charge the Army with administration. Pinchot appalled Sargent with a threat of a minority report to air his opposition to Army control. On May 1, 1897, six months after the due date, the Commission’s second report recommended that these lands “must be made to perform their part in the economy of the Nation” and called for “a permanent Government administration by officers of the highest character, entirely devoted to duty,” under the Army’s jurisdiction. Western senators tried to abolish the reserves, which were all in the West, but were headed off by the Pettigrew Amendment to the Sundry Civil Act of June 4, 1897—or the Organic Act of 1897. The amendment opened the reserves to regulated use, saying: “No public forest reservation shall be established except to improve and protect the forests within the reservation, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flow, and to furnish a continuing supply of timber for the use and necessities of the citizens of the United States.” It gave the Secretary of Interior authority to “regulate their occupancy and use and to preserve the forests therein....” It provided for the sale of “dead, mature, or large growth of trees” after they were “marked and designated.” In June of 1897, Pinchot was appointed a Confidential Forest Agent to examine the reserves, determine their circumstances, relate that to local economies, develop guides for additions to the reserves and prepare plans for the establishment of a professional Forest Service. He was paid expenses plus $10 per day. During the next year, Pinchot traveled the West increasing both his knowledge and range of political contacts. He crossed paths with John Muir in Seattle, Wash. From that meeting, a legend grew. Muir’s biographers say he confronted Pinchot over statements that appropriately regulated grazing of sheep might be acceptable on the reserves. Muir asked if the reports were accurate. Pinchot said they were. Muir is quoted as saying, “In that case, I don’t want anything more to do with you. When we were in the Cascades last summer, you yourself stated that the sheep did a great deal of harm.” Thus began the legend of the beginning of the conservation/preservation split. Historian Char Miller debunks that myth, saying that Muir, while preferring total preservation, understood Pinchot’s position and considered it rational. They continued a friendly relationship until the 1905 decision to build the Hetch Hetchy dam to supply water for a growing San Francisco. Muir strongly opposed the dam; Pinchot

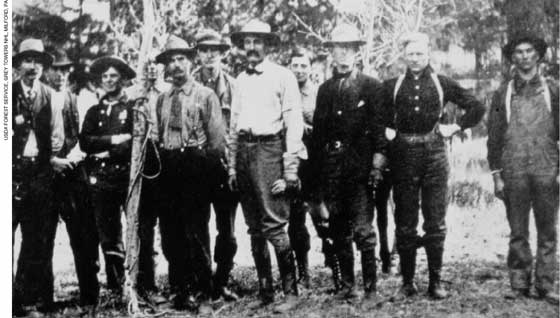

supported it. But the myth of the split between Muir and Pinchot over grazing contrasted purity and pragmatism in the management of the federal estate, and was simply too good a myth to die. These splits continue to define the debate between wise-use and preservation of the public lands. On July 1, 1898, Pinchot became Chief of the Forestry Division in the Department of Agriculture. In his autobiography, Pinchot professed not to have wanted the job. He accepted at the encouragement of others only after he attained Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson’s promise that he could run the division entirely as he saw fit. Pinchot assumed a unique title, that of Chief Forester. He renewed efforts to gain control over the forest reserves. By 1898, Theodore Roosevelt (TR) was governor of New York, famed as the commanding colonel of the Rough Riders in the Spanish American War. He was a rising star in the Republican Party. In 1897, Pinchot was sponsored by TR for membership in the Boone and Crockett Club, founded in 1887 under TR’s leadership. The select membership was active behind the scenes in most of the significant actions in the conservation arena from 1889 through 1918. Pinchot continuously prepared for the day he would attain control over the reserves and could assure their productive management. His family (in order to provide Pinchot with the people he would need) established a forestry school at Yale. Pinchot’s Forestry Division encouraged those students to apprentice in the field at $25 per month plus expenses and interest soared. They were to become the stalwarts that Pinchot would rely on. In 1899, Secretary of Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock asked Pinchot for advice related to livestock grazing on the reserves. Grazing was the most significant use being made of the reserves and the source of most conflicts. Pinchot considered the woolgrowers as the best politically organized entity in the West, who had shown their power by overrunning the Secretary of Interior’s decision to cease grazing on the reserves in 1897. Pinchot organized a three-week tour of key areas in Arizona and determined the best course was “to control sheep grazing...not shut it down. To regulate grazing is usually far better than to forbid it.... We were faced with this simple choice: shut out all grazing and lose the Forest Reserves, or let stock in under control and save the reserves for the nation. It seemed to me but one thing to do. We did it, and because we did it...national forests today safeguard the headwaters of most western rivers.” Pinchot’s efforts to gain control over the reserves shifted into high gear on September 14, 1901 when President William McKinley died from an assassin’s bullet. Theodore Roosevelt, who had been buried in the vice-presidency by Republican political bosses (who called him “that damn cowboy”), became president. Pinchot helped draft the new president’s first address to the nation, wedding TR to two points related to the reserves. “The forest reserves will inevitably be of greater use in the future than in the past. Additions should be made to them whenever practicable, and their usefulness should be increased by a thoroughly businesslike management.” Roosevelt also called for the reserves to be transferred to Agriculture. By 1903, Pinchot had not succeeded in transferring the reserves through frontal attack, so he suggested to TR a Committee on the Organization of Government Scientific Work, that might “serve to bring the Government forests and the Government foresters together in...Agriculture.” Roosevelt agreed and appointed Pinchot secretary to the Committee (by now, a clear modus operandi). As intended, the committee recommended that the reserves be transferred to Agriculture. Pinchot’s efforts paid off on February 1, 1905 when the Transfer Act moved the reserves to the newly created Forest Service (FS) but dropped recommendations calling for regulated grazing and the charging of a moderate fee. On the day that TR approved the Act, Secretary of Agriculture Wilson sent a letter (actually written by Pinchot) to the Chief Forester directing how the national forests were to be administered. It concluded, “local questions will be settled upon local grounds; the dominant industry will be considered first, but with as little restriction to minor industries as...possible; sudden changes in industrial conditions will be avoided by gradual adjustment after due notice; and where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.” A manual was distributed to Forest Service employees on July 1, 1905. Titled “The Use of the National Forest Reserves” and quickly renamed “The Use Book,” it replaced the Land Office’s Forest Reserve Manual. Pinchot delighted in contrasting the first sentences of these publications. The first said, “The Secretary of Interior...has the right to forbid...all kinds of grazing therein.” In the newer one: “The Secretary of Agriculture has authority to permit, regulate, or prohibit...grazing therein.” There, again, appeared Pinchot’s mantras—permit and regulate. Pinchot had three objectives: (1) protection and conservative use of lands adapted for grazing; (2) the best permanent good of the livestock industry through care and improvement of grazing lands; and (3) protection of the settler

and homebuilder against unfair competition in range use. Overgrazing was common and required dramatic reductions in numbers of livestock. Where that was necessary, the interests of small owners came ahead of those of large owners. In addition to regulating numbers, Pinchot—in spite of previous failures—set out to charge a fee for grazing to offset the costs of administering permits. Three months after the passage of the Transfer Act, Pinchot prepared a letter to Attorney General William H. Moody asking for a clarification of authority related to establishment of a saltery for preserving fish and Alaska’s national forestland. It was a subterfuge. The attorney general responded in only two days, that “you are authorized to make a reasonable charge in the connection with the use and occupation of these forest reserves whenever, in your judgment, such a course seems consistent with insuring the object of the reservation and the protection of the forests thereon from destruction.” Pinchot immediately applied that opinion to establishment of grazing fees. When western senators and representatives became aware of Pinchot’s ploy, they demanded a meeting with the Forest Service brass, Pinchot, and the president. TR rebuffed their objections and there was no effort to affect a legislative override. Two years after the Transfer Act of 1905, there was enough animosity in the Congress toward the Forest Service and Pinchot to allow the passage of a rider called the Fulton Amendment to the Agricultural Budget Bill, which TR would be loath to veto. The rider prohibited establishment of any additional national forests within Oregon, Washington, Montana, Colorado, and Wyoming. TR had one week between the time the bill was delivered and he had to sign or veto and gain a likely congressional override. With TR’s wink, Pinchot’s professionals clandestinely prepared the documents necessary for the addition of 16 million more acres to the national forests. TR signed the appropriate documents late in the evening of the last possible day before he signed the bill that prohibited such actions in the future. Roosevelt called these his midnight reserves. Within two weeks, the Colorado legislature called for a convention aimed to counter the TR/Pinchot coup—a showdown over who controlled public lands. In the end, the resolutions from the convention simply called for a review of policy related to management of the public estate. The Resolutions Committee had been stacked with members sympathetic to the TR/Pinchot line. The tidal wave of opposition was spent. As the fledgling Forest Service moved ahead with grazing regulation, including fees, direct challenges to that authority mounted. Pierre Grimaud, a California sheepman, was charged with illegally herding sheep onto the South Sierra National Forest. Almost simultaneously, a cattleman from Colorado, Fred Light, was caught running some 500 head of cattle on the Holy Cross Forest Reserve in direct defiance of a district court injunction. The Colorado legislature voted to underwrite the legal cost of Light’s challenge. Both cases came quickly to the supreme court, which upheld the authority of the Forest Service. As historian Char Miller noted: “The policy ramifications of these legal triumphs were immense. Henceforth, the Forest Service could...issue restrictions on grazing to improve soil fertility and the stability of watersheds, implement...scientific studies to determine how to preserve and use western lands, and develop reforestation and revegetation programs....” Pinchot served five years as chief of the Forest Service. Oddly, actual on-the-ground management was largely related to the establishment of authority regulating grazing, instituting fees for such grazing and application of those authorities. Controversies that arose from those actions continue today. Whether one admires or abhors Pinchot and his legacies, clearly his leadership in the conservation movement, including establishment of the Forest Service in his image, had lasting impact on livestock grazing in the American West. Jack Ward Thomas is the endowed Boone and Crockett Professor of Conservation at the University of Montana, Missoula. A research wildlife biologist, he retired as Chief of the Forest Service in 1996 after being one of two FS scientists in history to attain the most senior rank possible. |

|||||||||||

|

Winter 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||