|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

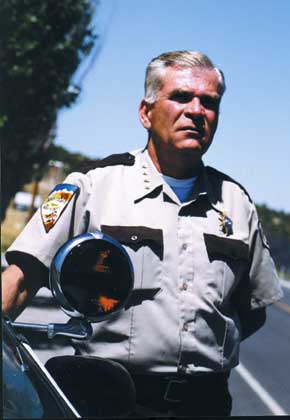

Cops are everywhere. These days in America, everybody seems to have a badge. But by common law at least a thousand years old, only the sheriff has elected authority over local law enforcement. The “MAN,” in some cases a woman, is still the bottom line on “legal” in some 3,000 jurisdictions of the United States. Even after the British in about the 17th century let go of the system of a “reeve” in every “shire,” it remained an essential element of English Common Law, mentioned nine times in the freedom-founding document of the Magna Carta alone and still generally acknowledged as the lynchpin of the American justice system. Next to the King himself, the “shire reeve” was the realm’s most powerful authority, not only in matters of law enforcement and tax collection, but in raising the “hue and cry” to rally the residents against a general threat, including that from another monarch. Robin Hood might recognize the ticket book as tax collection on a country highway, and most common country drunks can testify after any weekend to the effectiveness of a night in “gaol.” Less recognized these days, however, is the sort of formal hueing and crying that pits a number of western sheriffs and their constituents against what they see as expanding authority of the federal government into local matters. In many a shire, the reeve has about had it with the feds. “They despise me,” Eureka County, Nev., Sheriff Ken Jones says of his federal counterparts in the law enforcement division of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. “I think they draw straws just to see who gets the dreaded duty of giving me a phone call.” “Aww, that’s just Ken,” reassures BLM Nevada spokeswoman Jo Simpson. “We get along just fine with Sheriff Jones, and we respect his office.” It’s not really fair that Simpson never has lost the creamy charm of her Texas accent and Jones doesn’t see the need to drop some of the more colorful expressions from his Navy experience. Even an indirect argument between them seems sometimes like a discussion between Sitting Bull and Custer. “What they really want is to extend federal authority over all law enforcement in the United States, whether local people agree with that or not,” says Jones. “Well, it’s ‘not’ in this county.” Brick-jawed, hawk-eyed and sailor-spoken Sheriff Jones will retire from office this year after 17 years on the job that made him not only the longest-serving sheriff of his county, but the senior officer by service

in the entire state of Nevada. He is the former president of the Western States Sheriff’s Association and undoubtedly the most outspoken critic in the West of what he calls in Navy terms, “Federal cluster -----.” He has seen them in a clumsy FBI swat team attempt to capture “Mountain Man” Claude Dallas in Eureka early in Jones’ tenure when despite his repeated advice that Dallas had already left the county, agents used a “flash-bang” explosive that needlessly wrecked the home and collected treasures of an elderly woman who, like Jones and many others in the tiny mountain town, had known Dallas for years. Dallas, accused of killing two federal game agents, was later captured in another state near where Jones tried to tell the FBI he would be. Still strongly robust in his 60s, Jones almost never carries a gun and seldom wears his hat. People in Eureka County just know him as “the law.” His dealings with the feds have irritated him most when he has been made a reluctant witness to repeated attempts by the BLM to seize the cattle of the Dann sisters on federal land. The Danns are Western Shoshone tribal members who have defied federal grazing laws on the grounds that the land belongs to them by treaty. Every federal attempt over several years has been met by protests, including one in which a Danns’ supporter lit himself on fire and charged at federal agents, only to be brought to the ground and subdued by Jones and his deputies. “They asked me then what I was going to do with him,” Jones says. “I said, ‘Nothing, it was you guys he was after, you do something.’” The BLM did file charges of assaulting a federal officer, but Jones refused to play any bigger part in it than what he saw as minimally keeping the peace in his county until the BLM agents packed up and left. “One BLM agent called me after one of those and said he thought it went so well between his people and my deputies that it gave him an idea of how to help us out,” Jones recalls. “He suggested we could deputize the BLM agents and whatever citations they wrote would bring all the revenue to Eureka. “‘Oh, you mean like you guys see a hay truck without a taillight or something,’ I said. ‘Yeah, traffic stuff, things out of hand...’ I told him to have his agents find the nearest payphone and dial 911, and I’d give them the same authority as everybody else in the county.” “Just Ken,” as the BLM is likely to dismiss him, won’t accept state or federal funds for setting up DUI checkpoints on holidays, something he sees as entrapment, and he has turned down offers of government money to expand and modernize the four-deputy force he has to cover Eureka County’s 4,000 square miles. “We’ve only got about 1,900 people who live here anyway, I figure we can handle it,” says Jones, who, if such an extreme need arises, regards himself as the Eureka County “swat” team, always on call. “Local people have come to me again and again about horse gathers or cattle seizures or property rights and asked me to defend them from their own government,” Jones says. “I can’t blame them. Sometimes, the government scares me, too.” However much the BLM may be looking forward to meeting Ken Jones’ successor after this year’s elections, it’s not just the colorful Eureka sheriff alone who has let it be known there are limits to federal authority. Just north of the Nevada border in Owyhee County, Idaho, a younger, more scholastic sheriff has produced a unique agreement between his office and the BLM, limiting where the feds may go in his county and whom they may take with them. It started when local ranchers complained to Sheriff Gary Aman that the BLM was providing escort and transport services across private land for environmental activists looking for grazing damage. The activists weren’t just well-meaning students out on a field trip. The bunch riding in a BLM van Aman himself pulled over outside the county seat of Murphy, were all connected to Jon Marvel’s Idaho Watersheds Project, a front for the fanatically cow-hating architect’s campaign to drive all grazing off public land. “In effect, the BLM was choosing sides in the biggest battle this county has ever seen,” says Aman. Marvel’s continuous petty complaints and lawsuits against Owyhee County ranchers over the

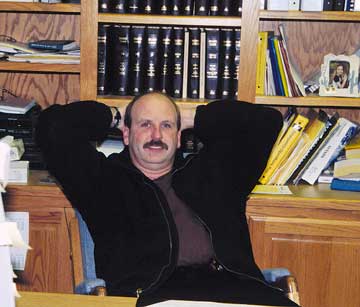

last five years had already become so nettlesome and pestering that the BLM itself had issued directives to employees not to talk to him. It must have been some consolation prize to offer his junior agents rides across private property in search of stream damage and evidence of overgrazing—problems the BLM itself seemed not to find. In July 2000, Aman issued a formal warning in his “no trespass policy” demanding that BLM obtain his permission and that of the landowner before escorting any nongovernment people across private land. The young sheriff made it clear he would not hesitate to arrest the activists and the feds if they ignored the policy. “I just said that I expect them to obey the law in my county the same way they expect ranchers to obey regulations on federal land.” Aman didn’t stop there. Like Jones, he made it clear that he didn’t want BLM help in local law enforcement and warned that he expected to be notified of any federal investigation or enforcement action, including impoundment of cattle the feds considered to be trespassing on U.S. property. Beyond that, the more cerebral Idaho sheriff produced accompanying paperwork leaving no doubt he would take the issue to court if necessary. “Part of my concern,” he says, “was that they were backing the ranchers so far into a corner that somebody might do something stupid.” It was the county equivalent of stopping the missiles bound for Cuba, and federal authorities at first stood blinking in disbelief as Aman and his county commissioners put forward a unified stand. The result was a

four-point agreement signed by District BLM officials giving Aman just what he wanted in requiring permission from the owner for crossing private land on general purposes, and permission from the sheriff himself two days in advance of conducting any “tours” by federal authorities. Any “enforcement” actions also require notification to the sheriff. The deal enraged environmentalists who had previously demanded BLM help in gathering evidence against the ranchers. The BLM resisted signing the agreement at first, but gradually seemed to find a little relief of their own in the details. Still spurred in part by Marvel’s relentless ranting and court cases, the relationship between the BLM and local ranchers they privately call “renegades” is only modestly better. After federal security alerts imposed by the 9/11 attacks in the East, Aman was dismayed to find Wayne Hage’s Idaho-based Stewards of the Range among a new list of “potential terrorist organizations.” “We get along okay now,” the cautious Aman says of the feds, “but nobody really thinks it’s over. And I’ll tell you what, it’s still scary.” To be sure, Marvel, never a friend to local lawmen, but politically pocket-close to Idaho Federal Judge Lynn Winmill, recently pressed his case into a finding by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco that the Owyhee Canyon lands are “overgrazed.” Marvel’s sometimes spokeswoman, Katie Fite, quickly gigged the ruling as a “nail in the coffin” of southwest Idaho ranchers, but still more appeals are pending. As with Aman, Sheriff Gary Penrod finds things “relatively quiet” since he and the BLM have come to their current understanding. In contrast to the classic boardwalk-town and mustang-roaming spaces of Ken Jones’ Eureka County, Penrod is in his third term as top lawman of perhaps the largest and most complex jurisdiction in the nation—San Bernardino County, California. Even so, Penrod shares some of the same problems with the BLM as Jones and Aman. What Penrod did, in effect, was fire them. The San Bernardino sheriff simply revoked local law enforcement

authority from the federal government across all 20,000 square miles of his county (an area five times the size of Ken Jones’ Eureka County) and advised them to consult him first before taking any action on private property. Thanks primarily to the plodding desert tortoise and another group of demanding environmentalists, that ended a long-standing agreement of mutual assistance with federal land agents and indirectly put the BLM on notice that Penrod’s own 1,600 sworn officers will at least stand with the rights of local ranchers as equals among the sheriff’s 1.7 million constituents. If such organizations as the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, Ariz., had not tried to imply their own federal authority in a campaign to prove that cattle endanger the habitat of the tortoise, things might never have gotten that hot in the Mohave. But it was just two summers ago when Range went along with Penrod’s deputies and rancher Dave Fisher to check on “turtle counters” near Fisher’s private land. The incident nearly went to court before Range photographs proved that the resentful environmentalists were not, as they claimed, hassled by armed deputies in “dusters” as they probed Fisher’s range. Penrod says that part of his decision came from just being fed up with the confusion created on county roads by federal agents “challenging the livelihood of people who have lived in the desert for generations.” Both sides seem to get along better now that the line is drawn on local authority, Penrod says. “I think we’ve been able to send out the message that we’re not going to be run over by Big Brother.” Local law officers all over the West have taken similar stands. In Utah, Sheriff Phil Barney drove a couple of hundred miles to recover cattle impounded by federal agents in the Escalante region and return them to their owner. Elsewhere in Nevada, guns were briefly drawn after a similar attempt at what local ranchers called “federal rustling” from another disputed allotment. Even at one of the last two ranches left in the glitzy shadow of sprawling Las Vegas, Cliven Bundy has the assurance of Clark County deputies that they’ll be there to defend his rights the minute the BLM acts on its years’-long threat to impound Bundy cattle for nonpayment of grazing fees and threats to endangered habitats. Nearly everywhere in the West, the bottom line is over federal attempts to reduce or further control grazing under already worn-out policies of Bruce Babbitt’s politically forced “range reform.” Earlier this year, the Department of Interior announced iü had entered in a new “Memorandum of Understanding” with the Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for up?dated training of Department law officers. A spokesman said the training would concentrate on protection of facilities such as dams and powerhouses in light of terrorist threats. But in a strangely self-conscious overstatement reminiscent of Babbitt himself, the news release from Washington, D.C. said Interior has “the third largest contingent of law enforcement officers in the federal government.” That’s true only if you lump more than 17,000 FBI agents and thousands more from drug enforcement and other agencies into the Department of Justice, and put another 10,000 customs officers as well as immigration agents into the Department of the Treasury. Only then are the 4,300 park police, rangers and BLM agents “third” in federal law enforcement. The BLM insists it doesn’t want a confrontation, and is not training for one with resisting ranchers. Most local jurisdictions hope, like Gary Aman, that the question of jurisdiction over land versus property in the “split estate” of the federalized West will be settled in court. A few, like Ken Jones, just stand by common law, and most, the truth be known, are happy just having nothing to do with it. But there’s a thousand years of proud tradition in what local citizens expect from their elected sheriff in almost every county of the country. It’s got at least 970 years or so over the vague origins of BLM law enforcement, and by all indications it’s not endangered yet. Just “threatened,” as sheriffs like Jones and Aman and Penrod see it. Tim Findley was stopped by a county sheriff in eastern Oregon after interviewing Sheriff Aman in Idaho. “So it helped a little,” Findley says, “to be thinking of Nottingham and Tombstone as well as certain sectors of the Deep South as I watched him dismount that flashing Ford and stride on up to my window that summer afternoon. History hurts. In this case, about 200 bucks worth.” |

|||||||||||||||

|

Winter 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||