|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

in Wyoming.” Someday they would go back there, maybe to visit, maybe to live, but it was a place where they would always be welcome when the rest of the world was collapsing into ruin. The grandfather was Jesse Johnson. He came from Ohio with his father and mother, wife and sibling to settle the ranch. Jesse Johnson was an amateur photographer, a man of a curious mind and wide-ranging interests, who died at age 34. Jim’s own father, Adair Johnson, left the ranch and rode the rodeo for a while after his dad died. Then a recruiter on a train between New York and Denver in 1929 talked him into joining the cavalry. He was sent to Fort Brown, Texas, married, and began a family. This was in the early 1930s and Jim remembers his dad riding past with the 12th Cavalry and the machine guns packed on mule back. Even though his dad was an enlisted man in the 12th Cavalry and they were living on a trooper’s pay, and the officers snapped out sharp orders to Adair, they were somebody. They had a ranch in Wyoming. All troubles and all setbacks were provisional, mere temporary inconveniences for people who own thousands of acres of prairie and mountain with shining horses running loose, only waiting for somebody to come and lay a rope on them, a country where delicate pronghorns with their white collars flash into invisibility among the rocky hills. When his dad quit the cavalry and went to roughnecking in the Texas oilfields, things got worse. Jim and his mother and four siblings once went without food for three days in Wilson, Okla. Jim remembers having to wear his dad’s house slippers to school because they were the only pair of shoes he had. When a big kid on the playground laughed at the house slippers, Jim knocked him down and held him by the ears until a teacher

separated them, because even if you are wearing house slippers to school and the only food you and your family had for the last three days was lettuce from the garden, the Johnsons were somebody. They had a ranch in Wyoming. His father and his uncle took on the most dangerous, ill-paid jobs in the oilfields as roughnecks. But still they kept their boots shined and on the weekends went to ride in the rodeos, because they were Wyoming cowboys, and Wyoming cowboys made American history, besides being glamorous and manly, and they never lost their dignity. Especially Wyoming cowboys whose family had a big ranch up there near Casper. My husband’s uncle Robert Oliver Johnson was standing over the drill stem once when a blowout occurred, driving sand up the pipe at the speed of bullets into his face and eyes. Robert could hear the casings roaring up the drill hole. He and every man on the drilling platform ran for their lives. Robert Oliver ran sightless through the

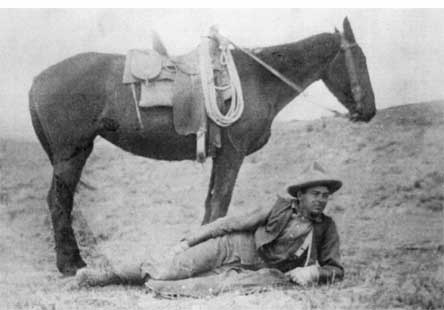

chaparral hearing pipe casings smashing to the earth on every side until somebody grabbed his arm and guided him to safety. He was permanently blinded in one eye. He was never able to ride the rodeo again. He was now disabled and took the lowest jobs offered, any job at all. But he came from people who had a ranch in Wyoming, in the grass country, and he shoveled ditches with great dignity. During their travels the Johnsons and their five children lugged Jesse Johnson’s books with them—grammars on the German and Latin languages, French dictionaries and an old encyclopedia from 1903, as well as albums full of pictures of the ranch. The books never got torn up, abandoned or sold. Jim and his brothers and sisters knew the photos by heart, the rocky rise of Pine Mountain and the earthen dam on the creek, they heard tales of old Caleb Johnson getting drunk in a Casper bar and offering to take on all comers. They knew the stories about the hard winters, the hunting cabin, about their father riding the rodeos even to Madison Square Garden in New York City. Crashing along rutted roads in a half-ton truck with everything they owned packed in boxes, on their way to yet another oil strike, the precious books and the photo albums were packed carefully at the bottom of a trunk, beyond the dust and heat. The Johnsons might be temporarily homeless, but they were somebody, because they had a ranch in Wyoming. During high school, Jim worked as a soda jerk and paperboy in Corpus Christi, Texas. He joined the Texas National Guard because he wanted to be an infantry officer, because the nation was still enthralled and grateful to the citizen soldiers of the American infantry who won the world back from the evil empires. Besides, people who have the kind of western property the Johnsons had, who come from the old traditions, have a duty to perform. Let the ranchers come in to the drugstore and retail all the gossip about the enormous King Ranch just south of Corpus Christi; let them go on about the Klebergs and their high-bred quarter horses, Wimpy and the Old Sorrel and Macarena. Jim served up sodas and coffee thinking, let them talk. He had a ranch in Wyoming, up there in the cool places. They had old family photos of it: men with sheepskin chaps, women in split skirts and Sam Browne hats, their throw-ropes coiled on their saddles and all their Wyoming land spread out behind them in a sea of grass. What do you wear if you’re “somebody”? He wangled an officer’s commission in the U.S. Army and went for the first time to the tailor’s to be measured for a uniform. The tailor was in San Antonio and they served him a scotch while he waited to be measured. He was not ill at ease. He and his new young wife might be nearly penniless but what the hell is money anyway? The Army issued a little booklet for the new officer and the officer’s wife as well, on deportment and dress. Jim learned not only what gentlemen properly wore and said, but instructed his sisters on the same. No young woman wears a black dress to a prom. He sent his younger sister back to the store with her black dress to buy another, because the Johnsons were somebody. They had a ranch in Wyoming. He rose to the rank of Captain in the U.S. Army and then one day his young wife died of a heart ailment and he was sent to Vietnam, leaving his two young children behind with their grandparents. He did what he was trained to do, wanted to do; he was a warrior, wasn’t he? And he came back from Vietnam with a Combat Infantryman’s Badge and a Silver Star and a Purple Heart only to learn that he was now a new phenomenon—the baby-killer, the crazed Vietnam Vet with PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). He managed to shrug that off. Didn’t he come from a family that had a ranch in Wyoming? Then once when he was on leave, before he married for the second time, he invited several friends to go with him to Wyoming. They’d drop in on the family ranch and go hunting. They would live like mountain men and set traps, bake biscuits in a Dutch oven in the fireplace in the old hunting cabin. He knew where the ranch was, his mother and father had pointed out the location to him many times on the map of Wyoming. At last his father had to tell him there was no ranch anymore. The ranch had passed out of the Johnson family’s hands half a century ago, to some cousins named Mann. His father was a very old man now, disabled by a stroke, and he confessed this to Jim with great reluctance, for the idea of the ranch had been their mainstay through terrible times, hard times, through poverty and injury and deaths. When Jim learned that the Johnson ranch had been sold many, many years ago, it wasn’t a shocking thing to discover at all. What had kept the family afloat was not money but hope and high standards, the dignity that comes from expecting more of oneself, the conviction that one comes from an old and honorable line who hold fast to the old traditions, from a people who are not flung up, down and sideways by any new fashion of behavior or belief. From people who can take risks with impunity because they are not alone in a world where everybody was born yesterday. The family story of the ranch made my husband, Jim, and all his family strive for the best in their lives. The no-longer-Johnson’s ranch had done its job. We all ought to have that interior geography. A sort of personal ranch of the imagination that gives one courage; an inheritance that no one can sell away from you or your family nor will it erode or burn and it can never be overgrazed. When you leave work today, think about it. Your ranch in Wyoming, expansive, broad, several thousand inner acres of waving grass, fat cattle, good horses and clear rivers. Pass it on. Paulette Jiles lives in San Antonio, Texas. |

|||||||||||

|

To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||