|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

||||||||||

| Time was when the U.S. Forest Service enjoyed an esprit de corps

equal to the Marines and higher than that of any other federal

agency–including the FBI and the CIA. Such is no longer the case–so

says retired and mildly disgruntled ex-forest ranger Joel Frandsen,

who proudly wore the green uniform for 34 years. “Most everything now is top down and politically driven,” writes Frandsen. “What once was a decentralized organization with most resource and personnel decisions made at the lowest possible level, is now orchestrated from the top down and from those outside the Service. The spirit has been altered. Leadership is lacking in the agency, the Department of Agriculture, and in Congress to get it back on course to meet its basic mission.” Frandsen’s disparaging words appear in the final chapter of an otherwise upbeat memoir: “Forest Trails And Tales: A Behind the Scene Account of a Career in the U.S. Forest Service.” For the most part, it is a tale of a man happy in his work and firmly committed to upholding the agency’s charter goal of Multiple Use-Sustained Yield. The job was especially rewarding in the early days of his career–back when most land management conflicts were still settled at the local level and when rangers spent lots of time in the field and not much time behind a desk. Frandsen’s adventures include stamping out forest fires, getting lost in a blizzard atop the Tavaputs Plateau, standing up to a belligerent lumberjack twice his size, struggling to maintain eye-contact with a comely resident of a nudist colony. And although he did his best to go by the book, not all of his schemes worked out according to plan. |

||||||||||

| Take sage grouse, for example. Interagency guidelines forbid activities

that might negatively impact the species’ strutting grounds. Conventional

wisdom holds that once the ground is disturbed, “the sage grouse

will all vanish and the world will come to an end,” writes Frandsen.

“If you’re charged with protecting these sites and something happens while they are in your care, you will be demoted, ostracized, or transferred to oblivion. Those are the game rules and like most good forest officers, I believed. I trusted, and I defended this truth with all my personal vigor and endured much personal scorn for my action which I knew was right. Wrong!” Frandsen’s confidence in conventional wisdom was shaken following a confrontation he had with an oil exploration outfit in northeastern Utah. Survey stakes had been driven and the bulldozers were ready to rumble, when along came Ranger Frandsen with the bad news that the drilling site would have to be relocated in order to safeguard the sage grouse. A tense standoff ensued between the oil company’s contractor and the obdurate forest ranger. Reinforcements from the U.S. Geological Survey were called in and a new field study conducted. Eventually a different drilling site was selected and a new access road laid out–one that would bypass the “sacred strutting ground.” |

||||||||||

|

enriched if we spent more time understanding the normal changes in nature, instead of trying to make nature conform to a set list of ‘protection rules’ of which many are inalienable truths and myths.” |

||||||||||

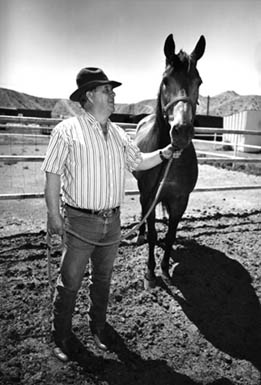

| The exploratory well came up dry, the drilling company moved on,

and the following spring during strutting season Ranger Frandsen

returned to monitor sage grouse activity in the area. To his surprise,

he discovered the birds had abandoned the strutting ground he’d

labored so hard to protect and had moved on to a new one–atop

the oil company’s drilling pad! “Since then,” concludes Frandsen, “I’ve always questioned the guidelines and haven’t been quite so zealous in adhering to these so-called inalienable truths. We would all be enriched if we spent more time understanding the normal changes in nature, instead of trying to make nature conform to a set list of ‘protection rules’ of which many are inalienable truths and myths.” Frandsen questions the wisdom of other public land management policies, in particular those championed by pro-wilderness groups including the Sierra Club and the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, with whom he had occasion to spar while working as a ranger on the Manti-LaSal District. “There are some real environmental issues, but they’re not dealing with the ones that, to me, are significant,” he says. “You know, you’ve got the groups that are just anti-grazing, against any commercial type use. They’re just trying like heck to push all the public land grazers off. But I think we’ve got to have a wider spectrum than what you’ve got between dense urban areas with wilderness to escape to. I really think we need to rethink our present course of urbanization. It seems there’s a rush to urbanize the West, and it’s turning the West into the East. And if we keep pushing, to force these people that are dependent upon the land off the land, well, then, we’re going to lose that open space.” Joel Frandsen lives in Price, Utah, close to his horse and not far from the unmarked graves of numerous notorious outlaws. A 40-year member of the Society for Range Management, he is also an avid student of western history, legends, and folk tales. To order a copy of his book, contact: Wild West Trails and Tales, 1785 East 800 North, Price, UT 84501. |

||||||||||

|

Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||