|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|

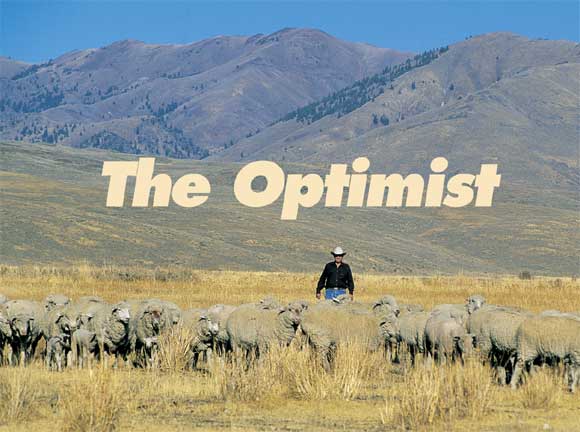

Sheep have grazed Idaho’s Pioneer Mountains and the Wood River Valley since the 1860s. |

John Peavey keeps life with sheep

|

| Omaha, Chicago, and Sioux City and Saint Joe, Kansas City and, later on, Denver and Ogden. It was a whole life of fraternity...there was tremendous competition not so much for the price you got, but the weight of your lambs and how good they looked. It was a real pride in doing business.”

Sheep and its challenging economics were on John Peavey’s mind, but no one else in the coffee shop shared his thoughts. We met because of the building’s history and, even more, because it’s an easy place for a visiting writer to find. Years ago, weathered denims, muddied boots and cowboy hats were part of the store’s, and Ketchum’s, character. No more. Passersby glanced at John as though he was out of place. “Let’s get out of here,” he barked, eager to show off his sheep range. Peavey was born to a life of sheep and politics on Sept. 1, 1933, in Twin Falls, Idaho. His grandfather, John Thomas, twice appointed a U.S. senator, began putting together the Flat Top Sheep Company in the 1920s. Art Peavey,John’s father, was a lawyer and the ranch’s operator who died when John was only eight years old. His mother, Mary, lived in Washington, D.C. and eventually married Senator C. Wayland “Curly” Brooks of Illinois. She served as director of the U.S. Mint under Presidents Nixon and Ford. Still, the family made regular visits to their Idaho sheep ranch. “I came back here every summer, even in college,” John says. “A lot of guys on the ranch helped to raise me.” |

|

Although John earned an engineering degree from Northwestern University, the ranching lifestyle was always part of him. So was politics. A maverick, he bolted the Republican Party—the political party of his grandfather, mother and stepfather—after six years and became a Democrat, serving 14 years as an Idaho state senator until retiring after an unsuccessful bid for lieutenant governor in 1994. It’s easy to pick him out from photographs of Idaho’s state senators and representatives—John is the only one wearing a cowboy hat.

We’re tromping up and down the hills on Forest Service-managed lease lands not many miles from Sun Valley. It’s spacious country with abundant vistas that in another region might be a national park. We stop at an enclosure where grazing animals have been excluded for 50 years. Compared to the grazed area outside, the plants inside are old and decadent. In the dense and gnarled growth there is no space for new seedlings. It’s a tinderbox. Outside, in the unprotected areas, are plants of all ages. John claims the grazed area is more likely to survive environmental threats. The plants are younger and healthier and there is less vegetation above ground that could fuel a fire.

“I think the Forest Service is as misguided on its grazing policies as they are on fire policies,” he grumbles. “Well-managed grazing enhances the watershed.”

We walk trails left by wildlife and livestock that contour the mountainside. He says the “micro-terraces” slow precipitation run-off, allowing water-borne soil particles to be held on the trails. As the water slows, more soaks into the subsoil in summer, where it can help spring flows and stimulate more hillside plant growth.

“I would like to see an environmental movement that recognizes that grazing complements the plants and the land and is really simply harvesting solar energy, and that recognizes that forage is the ultimate renewable energy.”

John Peavey and his wife, Diane, don’t have many secrets. That’s because many of their stories have been told on her weekly Idaho Public Radio broadcasts. Many are collected in her 2001 book, “Bitterbrush Country: Living on the Edge of the Land,” a compilation of 12 years of radio tales.

“You go on the radio and 50,000 people are listening to you every week. To be able to reach so many with a

Diane Peavey fries eggs, bacon and potatoes in the ranch house that was created from three 100-year-old cabins moved from an old mining site. |

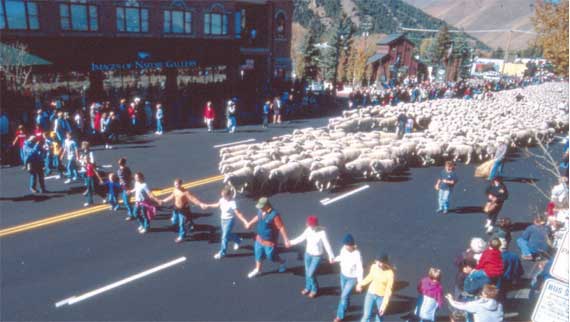

message for the land is amazing,” says Diane. “Instead of being ‘Cowgirl of the Year,’ this is my outlet, my way to reach people. It isn’t about roping, riding and castrating. The thing that appeals most to me is communicating, building bridges, helping people understand each other. That’s the best thing I can do for this ranch.” She and John met in 1980 and, after their marriage a year later, moved to his family sheep ranch in the foothills of south-central Idaho’s Pioneer Mountains. Depending on the season, they shuttle between the ranch, an apartment in Ketchum and seasonal cattle operations in Kimama, 75 miles south and, through the depths of winter, leased winter sheep range near Madera, Calif. Together, Diane and John have become local celebrities because of their successful efforts in developing the Trailing of the Sheep Festival, an October celebration created to ease tensions as trophy homes and golf courses are built along the edges of historic sheep trails. Now a bicycle path, the trail is still used each spring and fall, although by fewer and fewer sheepmen. Sheep were brought into the Wood River Valley in the late 1860s. By 1890 there were 614,000 sheep in Idaho and by 1918, 2.7 million. Based on recent estimates, Blaine County, which includes Ketchum, Bellevue and the Peavey ranch, has 32,000 sheep and lambs, the most of any Idaho county. Other estimates set the number of sheep at 260,000 state-wide. Interestingly, 40 percent are on smaller farms, not on larger range operations. |

“The market is here,” Diane believes. “People come and they want fresh lamb, Idaho lamb.”

It’s 24 mountain miles from Bellevue to the Flat Top Sheep Ranch, dirt road all the way. The Flat Top isn’t a place you visit accidentally. John chuckles, “It’s a humbling experience when you’ve got so many miles of driveway.”

The road was originally used in the late 1800s to haul silver from the Muldoon mines, located in the hills near the Flat Top. Later, it was traveled in a horse and buggy by James Laidlaw, a herder who built his own sheep and cattle operation. Laidlaw also developed the Panama breed, a cross of Lincoln ewes and Rambouillet bucks, and brought the first Suffolk sheep into Idaho. His old headquarters serves as the home ranch for the Peaveys. Until John bought the Laidlaw property with its Black Angus cattle in 1960, the Peaveys’ sheep operation was transient. They lived in town, traveled to the mountains and used a log cabin with a sod roof on Baugh Creek to store saddles and equipment. They lived on the range in sheep wagons.

“When I was 13, 14, I’d tie a bedroll on the back of a saddle and head up the Little Wood River to help the herders. I’d be gone one, two weeks sometimes,” John says. “Come back all dirty.”

Life is easier, but hardly plush. The ranch house is unique, a composite of three 100-year-old cabins that were long ago moved from the old Muldoon mine site. It sits yards away from Friedman Creek, nestled in a grove of cottonwoods. Because of its remoteness, and because the sheep move south for the winter, ranch operations are buttoned up in mid-November.

Sheep manager Denny Burks, who succeeded his father and grandfather on the Flat Top, follows the sheep as they’re trailed south to Kimama and later trucked to central California. One of John’s sons, Tom, 37, lives on the ranch near the headquarters area and is taking over more of the day-to-day operations. “Tom’s awfully good with computers and budgets and farming,” John quietly boasts. “I need to be gone a lot more.”

Even more softly and wistfully, John speculates on the ranch’s future and ponders whether Tom’s son, Jake, his grandson, might eventually be the Flat Top’s fifth-generation owner—“He seems to like it.”

The Flat Top has 30,000 deeded acres along with thousands of acres of allotments. Sheep are the focus of the

|

| Youngsters with linked arms lead the way through downtown Ketchum, Idaho during the annual October Trailing of the Sheep Festival. |

operation, with about 4,000 ewes. There’s also 1,000 Black Angus cows and 1,500 yearlings. The Peaveys grow 2,000 tons of hay and produce an equal amount of silage.

The ranch and its sheep follow a seasonal cycle. In early April, after lambing in California, the sheep and their young are trucked to desert lands between Kimama and Carey, where they spend six weeks fattening before being divided into four bands, with 1,500 to 2,000 sheep in each band. Guided by herders and their dogs, they make the 30-day journey north toward the ranch and, eventually, the Pioneer Mountains. The sheep graze at elevations between 9,000 and 10,000 feet above sea level from mid-June to mid-October, when the ewes are sheared and preg-checked by ultrasound. In July and August anywhere from 4,500 to 5,000 lambs are sold and delivered to feedlots in Colorado. The remaining ewes and bucks, usually grouped in two or three bands, reverse the migration, gradually moving from the mountains to the ranch, at 6,000 feet, and Kimama, about 4,000 feet, before being trucked to central California. On each migration the sheep and handlers cover about 80 to 90 miles.

The cattle, John believes, add diversity to the ranch and help utilize different food sources and terrain. “They really complement each other,” he says, explaining how cattle prefer meadows and grasses while sheep graze on hillsides and favor weeds and flowers. “I think they work together well.”

Breakfast is later than usual this morning. The afternoon prior, just a few hours before sundown, John spied smoke billowing from the trees near Tom’s house. When we arrived, a mysterious fire was roaring out of control. It had escaped the barrel and spread quickly, threatening the house and a nearby sheep corral. It seemed ready to run amok, especially after the blaze reached a propane tank that caught fire and consumed its leftover fuel, belching as loudly as a 747 readying for take-off. Flames from the tank fried an overhead power line, cutting off electricity to a water pump and forcing us to make an impromptu bucket brigade to protect the house. Close to midnight, after rigging a series of hoses from operating pumps, moving vehicles out of the line of fire, gradually gaining reinforcements and, well after dark, turning operations over to volunteers from the Carey Fire Department, the blaze was subdued.

“Tom’s got a great view from his house now. He’s thinking of building a deck,” Diane tells me later, referring to the unplanned clearing where a thicket of trees and tall shrubs had surrounded Tom’s house.

|

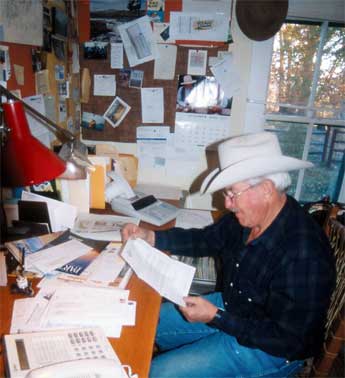

John and Diane may be celebrities in Ketchum for the Trailing of the Sheep Festival or, years past, at the state capitol in Boise, but on the ranch they’re two people facing daily challenges. Before eating breakfast, John sits at the desk making telephone calls and paying bills while Diane plans a trip to a meeting in Ketchum, with a quick stop in Carey to deliver grandson Jake to school. After breakfast, John is back in his mobile office—his pickup truck. “I don’t care how many problems you’ve got,” he explains, easy behind the wheel. “You’ve got to get out here on the land. It puts things in perspective.” What is John Peavey’s perspective about the future of sheep? He mentions an ongoing drought in Australia that could impact wool and lamb imports into the U.S. from “down under,” the weakening U.S. dollar worldwide making U.S.-grown commodities more competitive with global markets and, as a result, increased demands for wool in China. “The acceptance of lamb as a specialty meat is also a real plus. I think the future is pretty good. Lamb prices are starting to rally. Wool has made a dramatic recovery. |

A sign in Ketchum welcomes sheep and fans to the festival. |

“I am,” Peavey insists, “a perpetual optimist.”

Lee Juillerat is a reporter/writer/photographer for the Herald & News in Klamath Falls, Ore.

|

Spring 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||