|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

Allen Clyde runs 200 head of cattle on a 10,000-acre permit in the John Muir Wilderness east of Shaver Lake in the mountains above Fresno. He also owns Clyde Pack Outfit and estimates he and his wife Deborah ride about 1,500 miles each season. They’ve packed in more than 10,000 people during the 22 years he’s owned the outfit. |

Cattlemen have summered their herds in California’s Sierra Nevada for well over a century. Recently, the effect of grazing on the high country’s flora and fauna has been questioned. A bird called the willow fly catcher, the yellow-legged frog and the Yosemite toad are thought to be on the decline, blamed in part on cattle foraging. While the mantra of applying sound science to environmental claims often seems to fall on deaf ears, one rancher is proving sound management practices can benefit both the ecosystem and the pocketbook. The key is local control. For six years Dr. Allen Clyde has run 200 head of cattle on a 10,000-acre permit in the John Muir Wilderness east of Shaver Lake in the mountains above Fresno. Clyde also owns Clyde Pack Outfit and estimates he and his wife Deborah ride about 1,500 miles each season. They’ve packed in more than 10,000 people during the 22 years he’s owned the outfit. While farmers and ranchers throughout the nation are bemoaning low monetary returns, rising input costs and government over-regulation, Clyde has seen a profit in his cattle and pack operations each year he’s been in business. His guiding principle is “keep ahead of the chores.” Actually there’s a little more to it than that. Clyde was born and raised in Clovis, Calif. He earned a degree in biology from Fresno State College and received his medical training in San Francisco. He’s had a surgical podiatry practice in Clovis for 26 years. He describes himself as an environmentalist who got into ranching in a roundabout way. In fact Clyde’s interest in ranching came from his packing experience. He began enjoying the mountains as a back packer and decided he’d rather ride than walk. |

|

Clyde sees an advantage in not being born into a ranching environment. “Since I didn’t grow up in this business I’m not burdened with tradition,” he says. “Medicine helped. It gave me enough financial backing to get started. I didn’t inherit any of this.” The area where Clyde runs cattle and packs has a long history. The pack outfit he bought is more than 60 years old and his current grazing permit belonged to the same family since the 1880s. There are more than 100 lakes, 200 miles of trails and about 3,000 acres of meadows in the part of the Sierra Nevada he works. The grazing controversy centers in these meadows. The willow fly catcher nests on the ground beneath small, brush-like trees called lemon willows that grow in the middle of meadows. This is a location with abundant grass. Some say grazing cattle can disturb the nests and that disturbs environmentalists. Cattle can also damage shallow ponds found in meadows where yellow-legged frogs and Yosemite toads make their homes. Endangered species can be a rancher’s worst nightmare. No one wants to see an animal disappear from the face of the earth, but no one wants a spotted owl nesting in their apple orchard or kit fox burrow on their grazing lands either. John Kleinfelter is an Associate Fisheries Biologist with the California Department of Fish & Game. He’s also the regional coordinator for the High Mountain Lake Project. The project is a statewide attempt to inventory, monitor and assess water in the mountains. “Frogs and toads breathe through their skin and are very sensitive,” he explains. “That’s why they’re called indicator |

. |

|

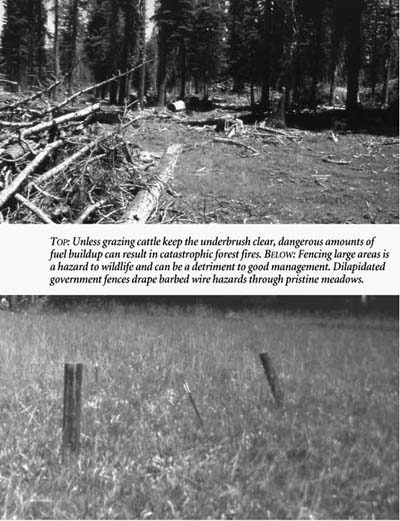

species. They’re the first sign of environmental decline. Yosemite toads prefer meadow ponds and utilize burrows. Grazing could trample the burrows and disturb the small ponds.” Kleinfelter said keeping the yellow-legged frog off the endangered species list is to everyone’s benefit. “If a species is lost it impacts the entire chain. It takes the wild out of wilderness, which of course, is what the packers have to offer. Our goal is to keep the environmental process natural.” One solution for protecting birds and frogs in the Sierra is to keep all cattle and horses out. Unfortunately that also ruins ranchers’ income and they then become the endangered species. One proposal was for the government to fence off the meadows; but that approach was labor intensive and trial attempts resulted in miles of barb-wire introduced into the natural settings of the meadows. Clyde has been working on a solution that includes both habitat protection and grazing. While he’s not ready to proclaim his system as the end-all of range management, he is definitely coming closer to refining a program that others can emulate. Again, he says it’s just a matter of “keeping ahead of the chores.” He says, “With the proper management the Sierra can handle three or four times the number of cattle that are permitted there now.” Cattle typically stick to the sides of meadows. Lemon willows grow in the center for maximum sunlight. Clyde says if fencing must be used, just fence off the willows. This saves both time and money in materials and labor as well as allowing grazing while protecting the nesting areas. Clyde rotates his herd so that cattle won’t be near ponds and burrows used by frogs and toads. Since the ponds dry up naturally during the summer, cattle can be allowed in certain meadows later in the year. He says his cattle have been “semi-trained” to stay in certain areas by the placement of salt licks. “That’s why I double ear-tag them. It makes it easier to see which cows are behaving. Some cows won’t be denied certain meadows. If they become a problem, they’re culled. There are too many good cows and horses to mess with.” He says concentrated grazing is good for his land. Without naturally occurring fires, brush builds up and chokes out other native plants. By limiting the area the cattle and horses graze, brush and other undesirable plants are removed as the livestock graze closely. “The animals don’t just cherry pick the best grass and move on, and leasing the extra land is actually cheaper than buying hay.” As streams meander through the meadows, ox bows, bends and switch backs slow the water flow and help fish and plant life. Because of the close attention Clyde pays to forage grasses and streams, riparian areas grazed by his herd are making a dramatic comeback. He speculates that the cowboy of the future will have to have a working knowledge of biology as well as roping, riding and other traditional skills. As in many parts of the West, Fresno County was designated a federal drought area in 2002. “By rotating three pastures |

|

we’ve never had a shortage of grass. Even with this dry year we’re getting along fine.” If low rainfall stunts grass growth, he is able to skip a pasture for an extra year and give the vegetation time to recover. He has been documenting his range management procedure and reports that so far native grasses and plants are making a strong comeback The key to his management is hands-on involvement. During the summer he cuts his medical practice by half to spend more time in the saddle. To keep the cost effective, he has only one non-family hired hand, Billy Prewit. Prewit says cowboying isn’t something he does for the money, “It’s a way of life, a good life. It’s because of the people I know. The Clydes are like family to me.” Clyde says with the right cowboy and a few “good” dogs it’s not that difficult to stay on top of 200 head ranging on 10,000 acres of mountain top. “After packing people 25 miles a day, doing a cow loop check is a vacation.” Raising his own herds of cattle and horses also save money. His pack string has 50 horses. Most were born and raised on his ranch. “I’ve got nothing against mules,” |

|

|

says Clyde. “But for the price of a good mule I can buy three horses. Most packers prefer mules, but for me it’s a business decision.” Because Clyde packs for the department of Fish & Game he and Kleinfelter have struck up a working relationship. After many miles and hours of conversation in the saddle they’ve had the chance to share ideas. “It’s unfortunate,” Kleinfelter says, “but some of the environmentalists set up confrontations. When I hear an environmentalist demand an end to logging, I tell him to move out of his wooden house and quit using toilet paper.” Kleinfelter and Clyde agree there is a middle ground in which a manageable balance between native species, recreation and commercial uses such as grazing can come together in the Sierra. “Clyde Allen understands how to manage effectively,” says Kleinfelter. “By including packers and ranchers in what we do, we both learn. And one of the things we learned is we can work together.” U.S. Forest Service District Ranger Ray Porter agrees. The Forest Service issues the necessary grazing permits and works closely with Clyde to find solutions that will allow the coexistence of grazing and endangered species. Each year ranchers must submit an operating plan in order to get their grazing permit. Permits are issued in early spring. This year, instead of prohibiting cattle from sensitive meadows, only the affected riparian and nesting areas will be fenced off, leaving plenty of room for cattle grazing. Porter says this is a specific approach to just Clyde’s allotment, but can be a model for other areas facing similar range management issues. Porter says, “Clyde Allen’s willingness to work with us and his attention to the science of eco-restoration have given us broader options than just saying yes or no to grazing.” There’s another environmental benefit of running cattle in the Sierra that’s often overlooked, Clyde says. In order to have a permit you have to have a base ranch. Clyde owns 1,000 acres and leases an additional 2,000 acres in the foothills near Auberry, Calif., where he winters his cattle and pack string. “Without summer high-country grazing I could only run about half my herd. The ranch wouldn’t make a profit, I’d have to sell. The only thing left would be to grow houses and the habitat is gone forever. The grazing permits are vital.” A major issue for California’s Central Valley is the loss of farmland due to urbanization. Some estimates predict an additional four million people will settle in the world’s highest-producing agricultural area within the next 15 years. Without substantial, contiguous areas of productive agricultural acreage this influx of population could spur leapfrog development. That will increase air pollution and other evils of mass urbanization, harming the environment far more than even the poorest ranch management. If that happens, it really will be tough for all of us, rancher and environmentalist alike, to keep up with the chores. Don A. Wright is a freelance writer from Clovis, Calif. His work has appeared in numerous publications including the Los Angeles Times, Oakland Tribune and The Business Journal. |

|

Spring 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||