|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

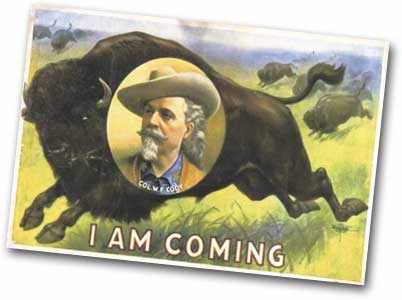

William F. Cody, better known to history as Buffalo Bill, invented the myth of the American West. Without Buffalo Bill the Plainsman, there would not have been “The Plainsman.” No books or television shows. No “Gunsmoke,” “High Noon,” or “Shane.” No John Ford, John Wayne, Gary Cooper or Alan Ladd as we know them. The dime novelist Ned Buntline—with a bad play called “The Scouts of the Plains”—conjured up the myth in 1873. The production starred Cody (at 27 already famous as an Army scout and contract buffalo hunter), his friends Texas Jack Omohundro and legendary Kansas lawman James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok, and a young Italian actress named Giuseppina Morlacchi, who played the innocent Indian heroine. The melodrama toured eastern cities and, despite pretensions toward seriousness, was considered a laughable farce. The newspaper reviews were uniformly dismal. Not only was the cast of inferior thespian ability, but Hickok often appeared drunk onstage, forgetting his lines or making up his own. One night a stage light was bothering his eyes and

with annoyance he pulled a revolver and shot it out, darkening the theater to wild applause. Another night, he drunkenly played a love scene with Miss Morlacchi all too well, his lechery causing a scandal in the papers. Hickok the actor was a sort of Victorian proto-Marlon Brando. Backstage, Cody, Hickok, Texas Jack and entourage behaved like rock stars; all night booze-fueled poker games, fights, broken furniture, cast members carted off to jail, and irate theater owners constantly mollified by Cody and Buntline. In Pittsburgh, Hickok got into a barroom brawl after the show, and gave a good account of himself against six men. This was an apt ending to “The Scouts of the Plains,” which had closed that night. Buntline and Cody paid off the cast and crew, and Hickok put his sorely bruised body on a night train west, leaving Buffalo Bill to reflect on the experience and mull over the possibilities of a future marriage of the mythic West and show business. The bug had bit. After gathering sufficient investment capital, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World” premiered in Omaha, Neb., in 1883. Because he sought to present the authentic West, Cody refused to label the

production a “Show,” fearing the audience might take the word to mean that the presentation was less than real. It would tour regularly until 1913. Over three decades its total cast and crew would number in the thousands. It would showcase at different times the riding or shooting talents of Pawnee Bill, Doc Carver, Johnnie Baker, Sitting Bull, Annie Oakley, wild Indians, cossacks and cowboys. At any one time the sagebrush impresario took 1,000 horses, 600 cast and crew, and tons of baggage to the great cities of North America and Europe. A long row of 20-foot stoves fed this army three hot meals a day. The genius of logistics—the man who moved the production like Napolean moved armies—was one Nate Salisbury, a much-wounded Civil War veteran and survivor of the notorious Confederate prison Andersonville. He had the knack of putting Cody and Company where they could be seen by the most people. Salisbury’s death in 1902 marked the decline of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. But for a street named for him in Cody, Wyo., he isn’t remembered much today. Buffalo Bill being a magnet for publicity meant that the troupe was forever having their picture taken, all over the world: New York, Chicago, San Francisco, London, Paris, St. Petersburg. He took advantage of new technology and had the show filmed with the new motion picture cameras. Many silent reels survive and can be found at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyo. As documentary history they are fascinating. One wonders if D.W. Griffith might have seen these short takes of trick riders and charging Indians and the long white-tressed scout himself waving to the crowd while mounted on a beautiful white horse. If Cody had been born a generation later, he might have ended his days a Hollywood mogul. The big draw—especially in European venues—were the Indians. In the states they were many times booed and jeered at as the killers of the sainted Custer, but in Europe were thought noble and brave. Sitting Bull, Iron Tail, Rocky Bear, American Horse, Young Man Afraid of His Horses—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had on the payroll some of the legendary stars of the Plains wars. Sitting Bull was particularly admired. He learned to write his name in order to sign—and sell—autographs,

This didn’t sit well with the Sioux who were to be in the movie, as they considered the Wounded Knee Creek area sacred ground. The wise and ever-faithful Iron Tail (whose handsomely noble features were the model for the Indian Head nickel) quietly informed his old friend Cody that there were rumors of warriors planning to use live ammunition, thus giving Miles (who would play himself) his just deserts and avenging their slain ancestors. Had this happened it would have made cinematic history. As it was, Cody diplomatically convinced Miles of the positive attributes of another location, the Sioux replaced bullets with blanks at Cody’s behest, and the general—unaware of the conspiracy—survived into boorish old age. The Indians died on cue in a forgettable production. In 1913 Buffalo Bill’s Wild West went broke in Denver. The new entertainment entity of Hollywood (which Cody had indirectly contributed to with his show filmings and reenactments) was capturing the American public’s attention. Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and their ilk cavorted on the silent screen as an aging Buffalo Bill glumly performed a poor parody of his former self with the Sells-Floto Circus, all the while suffering health problems. His uremic poisoning flared up as he visited his sister May Decker in Denver in January, 1917. A local doctor gave the legendary 70-year-old hard-living impresario 36 hours to live, and to the annoyance of May—a pious woman interested in prayer and a deathbed vigil—Cody called on friends present for one last big poker game. On a cold winter day the most famous man in the world exited the stage in character. Bill Croke is a writer in Cody, Wyo. |

|||||||

|

Spring 2003 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 03.29.05 |

|||