|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|||

|

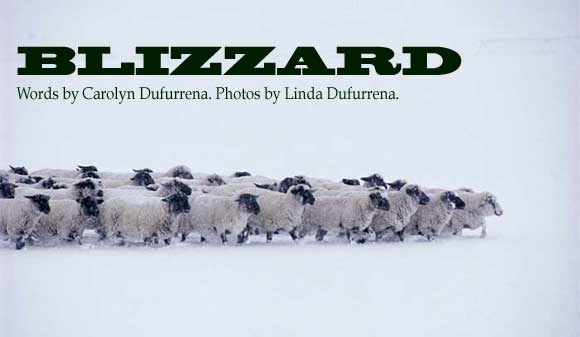

Once the sheep leave for the winter country, they are gone. Each day the trail takes them further south, one, two, three long valleys away, down gravel, and then not-even-gravel, roads. Someone drives down every few days to move the herder’s camp, in winter a little white metal house on wheels; take him a pair of boots, some oil, and more batteries. It is vast empty country, even by our standards, those valleys that fringe the Black Rock playa. “Oh, not until March,” the man who sold them the new sheep had assured them. “They won’t lamb till March, maybe early April.” It should have been a good deal, those older ewes. Buster and Hank had agreed, and now the sheep are well on their way to the winter country. The truck rumbles south, heater roaring, trying to keep up with the wind. It’s an arctic wind, stronger by the hour, blowing in the seams and cracks, chilling the windows. The ruts are frozen today so the trip is rough, but Hank won’t get stuck. The horse trailer creaks along behind. We passed the last of the widely scattered ranches the better part of an hour ago. The road snakes through low gray hills, an interference of little waves between mountain ranges. As the snow starts to spit, we come upon a small enclosure, steel posts and wooden pallets, in the middle of this empty place. In it are perhaps 10 ewes, heavy with winter wool—and lambs. A sheep does not show the closeness to her lambing in the same way as other animals. She will carry lambs five months, but a month from parturition looks like three, and although these sheep should not be close to lambing, some have already given birth, and the rest of them could start at any time.

Hank stands in the icy wind, untying the makeshift gate with freezing fingers. He wades into the bunch, lifting the old ewes into the trailer. They are stubborn, resentful. They just want to find a bush to tuck their lambs under, but there is no cover here. It’s not lambing country. The lambing grounds are two months and seventy miles’ slow grazing up the trail to the north. No one would choose this, but this is where they have found themselves, the sheep and the men who care for them, and there is nothing for it but to get through it. The last old ewe lay stubbornly, huge, a gray lump on frozen earth. “Come on, get in the trailer. Stand up.” My brother-in-law’s hands were red, cracked. The wind flung pellets of snow sideways. Soon the storm would be on us. The ewe groaned. In two hours he could have her home in the comparative warmth of the barn, straw on the floor, a pallet pen, a heat lamp, companions chewing hay next door. The first lamb slid halfway out in one push. “Oh, hell,” said Hank, more a prayer than a curse. He shut the door of the horse trailer. I walked to the cab to see if there was something to use for a towel. I came back shaking the dust out of an old gray sweatshirt crammed down behind the seat. The first lamb was out, sopping, quivering in the thickening storm. I remembered the frozen corrals at home, a tiny white lamb frozen solid to the ground before he could stand up. The men stood in a knot around the ewe, waiting. It didn’t take long. In a few minutes the second lamb slipped out. The ewe lay still, staring at something in the distance. “They can’t live, can they?” I asked, looking at the frozen earth that had received the early babies. He sighed. “They can take a lot.” One massive hand clanged open the trailer door. The lambs’ heads wobbled. Incredibly, they woozily clambered to their feet as Hank sunk his other hand into the deep wool of the ewe’s shoulder, one knee under her. He levered her hundred and eighty pounds into the trailer. The two lambs stood, feet apart, shaking their heads, tasting the dry, cruel desert snowstorm. The wind blew harder. We lifted the babies in next to their ancient mother, shut the door on them, and turned for home. And so the ewes kept lambing, in the winter desert, life coming against all odds, against all common sense. Hank or his father, or both of them, made the drive, once, sometimes twice or three times a day. Sometimes it seemed as though there

had never been any other existence than lifting the ewes in the freezing cold, into the horse trailer, into the back of the pickup. Hank tied a string around the leg of the ewe, and around the corresponding leg of the lambs, to identify the pairs. They seemed to forget each other in the first day of their common life: a string around this front leg of this pair, around the neck of that one with twins. Load up, bump off up the road, hours to the ranch, unload, come back, move the panels and the steel posts from their frozen place between low hills to another frozen place between other low hills. The band moves like a slow cloud across the desert landscape, southward before the winter wind. Ewes that lamb cannot be left behind to rest, as a lambing ewe should be allowed to do. The lambs cannot travel for a day or two, but in this country they will not survive a day or two in isolation. Coyotes, bobcats, cougars are all hungry in winter. So Hank spent that winter ferrying the old ewes home, through wet snow, flat tires, failing fuel pump. Once home, lifting them out of the truck, into the barn, building the honeycomb of wooden pens that will shelter them—and separate just the one ewe, and her lambs from the others—until they learn each other’s warmth and smell. Fresh hay, another pan for water, another stretching extension cord, and another heat lamp wired to the beam or to the nail in the wall. Build the pen, unload the sheep, feed and water, gas up the truck, and go again. January, February, March. This day was only one day in a long string of days, the product of all the days that had come before, a foreshadowing of days that were to come. But the sun still made its progress through the sky, and each day it warmed the earth a little more. The sheep turned around at last, and made their long, slow way back north, to the home ranch, to the lambing grounds, to the relative kindness of the spring. n Excerpted from “Fifty Miles From Home, Riding the long circle on a Nevada family ranch.” Photos by Linda Dufurrena. Text by Carolyn Dufurrena. University of Nevada Press. First edition sold out within weeks. Second edition available from RANGE in May (see ad page 71). Call 1-800 RANGE-4-U. Autographed copies also available. |

|||

|

Spring 2002 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||