|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

Lewis and Clark made history with every step they took, but no state played as rich a role in their experience as Montana. By Tom Daubert. Photos by Chad Harder.

Lewis and Clark spent more time and experienced more pivotal moments in present-day Montana than in any other state. During the planned, four-year celebration of the Expedition, beginning in 2003, Montana will be the only state along the route to host more than one of what the National Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Council has defined as “signature events.” In honor of the upcoming Lewis and Clark Bicentennial, the state’s ranching community is making history of its own—by producing a lasting legacy of environmental and historic-site protection through a program called Undaunted Stewardship. The program’s name derives from a phrase of Thomas Jefferson’s describing the Corps of Discovery’s leadership as having “courage undaunted.” Of all the states Lewis and Clark explored, Montana, more than any other, still looks as it did then. Beautiful, unpeopled, most of Montana consists of grassland prairies, the majority of which remain unchanged, in large part because of generations of family ranching. That’s why people today can float down the Missouri River reading the Lewis and Clark journals, and look up from their books to see views just like the ones described nearly 200 years ago. Undaunted Stewardship, quite simply, aims to keep it that way. “Undaunted Stewardship is a land management program that’s entirely incentive-based, with nothing regulatory about it,” says its director, Jim Peterson, a past executive vice-president of the Montana Stockgrowers Association, now working in affiliation with Montana State University. “We’re protecting and improving the environment, protecting special places, and keeping land in agricultural production at the same time.” At Montana State University, a land-grant institution renowned for its range and animal science programs, experts are helping ranchers refine their land management and environmental monitoring programs, certifying those who meet Undaunted Stewardship standards. Showcase ranches along the Lewis and Clark Trail system will provide heightened understanding of the values of stewardship and ranching. These private landowners pledge to continue preserving historic sites, and to ensure opportunities for the public to enjoy these sites. In exchange, they receive financial assistance to manage tourist impacts like the spread of weeds,

and to make environmental improvements that ranching alone can’t support. The program also helps interested ranchers develop sideline businesses to serve tourists, thus helping to keep ranching—and rural communities—alive. The idea for Undaunted Stewardship emerged from the Montana Stockgrowers Association. Ironically, it started with a government proposal the group didn’t like. But instead of reacting purely in the negative, they turned it around and grew it into something hugely positive, very ambitious—and utterly unique. Then-Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt floated the Missouri Breaks with renowned historian Steven Ambrose, whose book on Lewis and Clark, “Undaunted Courage,” was a bestseller at the time. Afterwards, Babbitt announced he was thinking of recommending the Breaks area for designation as a National Monument. The place was a national treasure, he explained, extraordinary in its natural and human history. In honor of the upcoming Bicentennial, it would be a good idea to protect it, finally. However nice it sounded, to the state’s ranching community Babbitt’s sentiment felt like splinters tearing into flesh. He seemed to imply that the Missouri Breaks were jeopardized by existing uses, when in the ranchers’ view the opposite was plainly the case. They felt his assessment of the area’s value and beauty was entirely correct, but the reason the area was still worthy of recognition was that ranching lifestyles were protecting it, as they had done for decades. To the people living and working on these landscapes, it was Monument status—Babbitt’s proposal—that would jeopardize the future of the Breaks. It would attract more of what was already starting to feel like a flood of tourists as the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial approached. That could produce negative environmental impacts, especially in remote places with little or no infrastructure. Such effects already were being felt. Yet the situation also presented an opportunity, which the Stockgrowers seized. If a flood of tourists was inevitable, why not put it to use? “The National Monument issue focused on only a relatively small area of federal land whose ownership and history of use already could ensure preservation,” Peterson explains. “But Undaunted Stewardship can address the entire state. Two-thirds of Montana, all along the Lewis and Clark Trail system, is privately owned, not subject to most government regulation, and most of it is rangeland.” The Stockgrowers believed it was time to celebrate and call attention to the fact that it is agricultural production that has kept most of Montana’s open spaces productive yet beautiful and preserved, with historic sites unchanged. “And,” Peterson continues, “to tell the world that not only have ranchers played a big role in keeping these places special, but that we intend to continue doing so.” Meanwhile, for Montana’s rural agricultural communities struggling to survive and to resist subdivision, tourism represented both an environmental impact problem to be managed and an economic and public education opportunity to be used. The goal of Undaunted Stewardship is a cohesive set of programs that will help “keep Montana Montana,” spread the word about the values of responsible ranching and build rural economies at the same time. The program is unique in several respects. Inspiration and initial development began in the private sector, but it has evolved into a genuinely cooperative program, directed and managed jointly by Montana State University, the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the Montana Stockgrowers Association. The federal-state-private-sector program addresses the majority of Montana’s land—privately owned—in ways no government program has yet contemplated. For one thing, it’s an entirely incentive-based program, non-regulatory. Everything participants do is voluntary. If ranchers choose to participate there can be financial rewards. The benefits of participating include protecting historic and natural resource values, while also keeping lands in agricultural production and supporting rural economies. The goal is to spread the program everywhere, especially along the Lewis and Clark Trail system. “It’s remarkable how well this ‘joint venture’ is working,” says John Moorhouse, Montana’s BLM representative on the program’s executive committee. “We recognize that good land stewardship has a great many rewards that

landowners and the public haven’t fully received. We’re hoping to help landowners take better advantage of the values they’ve created, and to help the public better appreciate them, too.” A guidance council that helps oversee the program’s policies and priorities includes leading conservation groups like American Rivers and the Montana Wilderness Association, working alongside representatives of virtually all the state’s agricultural groups and state and federal agencies. Some of the groups involved have historically spent their time fighting each other in court. Today, they’re finding consensus in the Undaunted Stewardship approach. “This is the first time in my career where a group as diverse as this has been able to sit around and agree on the use of significant dollars for a land-management purpose,” Peterson says. “It’s been truly cooperative, a shared goal. No one’s out talking to lawyers or figuring out how to outsmart anyone. “The land-grant university system’s involvement is central. Landowners trust the university extension people because they’ve worked with them for years. Relationships are different than with federal or state regulators. So folks now are sitting around the kitchen table with that feeling of trust, making decisions that have positive 10-year-plus consequences for the environment and the agricultural economy, and they are doing it with great excitement and anticipation. This is a rare opportunity.” Jeff Mosley, a Montana State University Extension Range Management Specialist, directs Undaunted Stewardship’s land-use programs. “We’re helping landowners refine their grazing plans and finding ways to increase the productivity and environmental quality of their ranches,” he explains. “It’s exciting to see ranches all over the state using state-of-the-science stewardship and monitoring the results of their land management.” Four flagship “showcase ranches” totaling over 117,000 privately owned acres have signed on—each featuring a site of major historic significance. Many more ranches are expected to become certified “Undaunted Stewards” and hundreds of other ranch families have expressed interest. Imagine standing on a spot where Lewis and Clark once stood, where Sacagawea once held little “Pomp” in her arms, knowing that the view in all directions is the same as the one they saw. Imagine being able to drive for days, knowing that most of the landscapes you’re passing look largely as they did 200 years ago—still natural, still abundant with wildlife and fish, still generating productive grasslands and waterways. Imagine knowing that your grandchildren—and theirs—may be able to do the same thing at the same places. You don’t have to imagine it. Undaunted Stewardship is helping to make it happen in Montana, today. First Four Showcase ranches, certified as superior stewards of their landscapes, will serve as focal points for a variety of activities connecting Lewis and Clark-related tourism with public education about stewardship and the environmental, cultural, economic and historic preservation benefits of ranching lifestyles. Interpretive displays will help visitors better appreciate the local historic and environmental values, and explain details of how ranch management sustains natural productivity. By the time the formal celebration of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial begins, special educational tours will be offered at some of the sites.

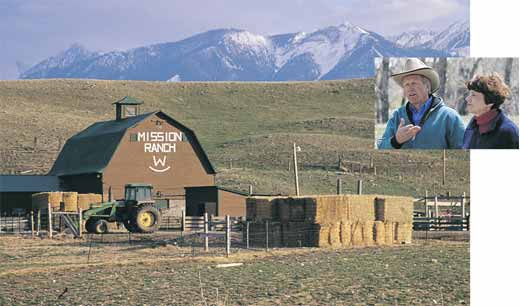

Pavlovick Ranch, Judith Landing Lewis and Clark camped here on May 28, 1805. Several key Indian treaties were signed here in later years, and the 8,100-acre ranch and its environs were home to Fort Chardon, Camp Cooke, Fort Clagett and the first ferry-crossing at Judith Landing. Area rangelands have been in continuous agricultural production since the late 1800s. With 2.5 miles of riverfront along the Missouri River, located at the end point for virtually everyone who floats through the new Missouri River Breaks National Monument, part of the Pavlovick Ranch receives some of the heaviest recreational use in this area of Montana. “We’re hoping Undaunted Stewardship can help us improve our service to tourists, as well as control the spread of weeds and make other environmental improvements we can’t afford from ranching income,” says Lacy Wortman, who manages the ranch with his wife Amy, a member of the Pavlovick family. The ranch plans to expand a small store that it operates for river recreationists, and to construct a primitive campground near its historic sites. Hilger/Sieben Ranches, Writing in his journal on July 19, 1805, Captain Meriwether Lewis named the “Gates of the Mountains” cliffs that frame the Missouri River where it passes the Hilger and Sieben Ranches. Central to the early history of the state’s livestock industry, the ranches encompass 104,000 private land acres—most of the scenery along a 30-mile stretch of interstate highway. “I’m hopeful Undaunted Stewardship can show visitors more about the reality of ranching,” says Cathy Campbell, who owns and manages the Hilger Ranch. Campbell is planting willows and cottonwoods along the riverbank, to recreate the kind of environment that would exist if dams constructed in the 1930s and later weren’t preventing the regular flooding that occurred at the time of Lewis and Clark’s passage. “We’re also doing horse logging,” Campbell says, “to restore range and create a more natural habitat for wildlife. Generations of fire suppression have let the trees get so dense that nothing grows well, habitat suffers, and the fire danger is serious. We won’t see the real fruits of these kinds of projects in our lifetime.” Beaverhead Gateway Ranch, On August 7, 1805, Sacagawea recognized Beaverhead Rock, marking a critical turning point in the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Seeing Beaverhead Rock meant they were entering territory frequented by Sacagawea’s tribe, so that horses the explorers needed might soon be at hand. Amazingly, a few days later, in present-day Beaverhead Valley, they came upon Sacagawea’s brother. By then he was a chief of the Shoshone, from whom his sister had been stolen years earlier. At the foot of this historic landmark, including rangelands and a recently developed wetland, the 1,080-acre Beaverhead Gateway Ranch has been in agricultural production since the mid-1880s. “What I’d really like is to preserve the historic value of the property, with a program to manage the vegetation to keep it as close as possible to what it was originally,” says Robert Peccia, ranch owner. “I expect the grazing and brush-planting plan that Undaunted Stewardship is developing will enhance the wetlands and reduce fire risks.” The interpretive display that the program is planning will be placed at a location that offers superior views both of Beaverhead Rock and of wetlands often teeming with pelicans, sandhill cranes, great blue herons and raptors. Mission Ranch and Fort Parker With two miles of Yellowstone River frontage, the 4,500-acre Mission Ranch lies across the river from a campsite that Captain William Clark used on July 15, 1806. In the late 1860s, the present-day ranch became the site of Fort Parker, where a treaty was signed establishing the Crow reservation—and making these rangelands home to the original Crow Agency. Parts of the present-day ranch have been in agricultural production ever since. Zena Ensign, a third-generation Montana rancher whose father bought the ranch in the 1940s, now manages it with her husband Doug. Both retired teachers—he of Montana history—the Ensigns are eager to use their ranching lifestyle and involvement in Undaunted Stewardship as a platform for public education about stewardship, history, and ranching. The Ensigns produce Black Angus beef and recently launched a bed-and-breakfast. They now offer fee-fishing on nearby Mission Spring Creek, whose fishery they have restored and improved partly with the help of Undaunted Stewardship. For a small access fee, they also allow fishing on their Yellowstone riverfront. The Mission Ranch has nominated the Fort Parker location for the National Register of Historic Places, and the Ensigns hope an Undaunted Stewardship interpretive display will help reduce litter and vandalism at the site. “You might say the Mission Ranch is on a mission,” Doug explains. “We want to honor the legacy of the people who came before us, and of the land and environment’s beauty.” Tom Daubert is a Montana-based writer and media and public relations/communications consultant specializing in environmental issues. He can be reached via his environmental weblog <http://bigskyview.blogspot.com>. Reprints of “Undaunted Stewardship” are available from Montana Stockgrowers Assn., in Helena at 1-406-442-3420. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fall 2002 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||